Metal and punk are commonly received as separate domains of musical activity, but there are many crossovers and consistencies between them. This was the primary charge of ‘Doing metal, being punk, doing punk, being metal: hybridity, crossover and difference in punk and metal subcultures’, a two-day conference held at De Montfort University (DMU) Leicester in collaboration between the Punk Scholars’ Network and the International Society for Metal Music Studies. Here’s a chronological write-up of the conference: in part a digest and in part my own recollections. Let me know if this kind of thing is interesting or useful!

As my first experience of the Punk Scholars’ Network, aspects of the conference organisation were aptly DIY, or more precisely DIT (that’s ‘do it together’): lots of getting lost in DMU’s labyrinthine Hawthorne building and bringing trays of cake to sessions to reduce food waste. Some four-paper sessions were scheduled for 1 hour and 15 minutes, which gave each speaker 18.75 minutes for the paper and questions. A couple of presenters commented that they had written 20 minute papers and had to either revise them on the fly or simply overrun. In that context, some might be wondering what’s wrong with the 20+10 format! This minor criticism aside, the conference was enthusiastically managed, and the programme included an admirably diverse range of topics. All heavy music was up for discussion, from a great variety of perspectives. By ‘heavy music’, I’m referring broadly to diverse forms of both punk and metal: the term indicates that the speaker examined various musics and music cultures within the punk and metal repertoire rather than focusing on a specific style.

Day 1: A morning of cultural politics

Lucy Rosemary Hill, who is soon taking up a post at the University of Huddersfield, opened the conference with an important keynote on how sexual violence maintains hegemonic masculinity in punk and metal, both in the mainstream and in local scenes. She pointed out that research on gender often means research on women, with too little understanding of men as gendered (drawing from Delphy on gender as a marker of division). It is necessary to consider the work men do to reinforce patriarchy and respond to feminism, particularly through musical works which present norms and shape cultural lives. In a sample of the mainstream rock and metal charts, only 2 of 60 songs involve women songwriters. While metal studies commonly focuses upon extreme music, the mainstream is an important domain of scholarly investigation because it is incredibly popular and often acts as a ‘gateway drug’ to other heavy music styles (which may be more explicitly problematic). Taking a definition of sexual violence as a continuum involving “threat, invasion, or assault” from Kelly (1988), Hill pointed out that women’s everyday experiences of music texts and heavy music scenes constantly feature “men’s intrusions” (Vera-Gray 2016). Female heavy music participants are asked to identify with male views (as the predominance of male songwriters exemplifies), but can adopt – and make available – new subject positions by, borrowing a phrase from Jasmine Shadrack, ‘performing back to patriarchy’.

Two speakers scheduled for panel 1.1, ‘Women’s Experiences’ were sadly unable to attend, so I opted for the panel including papers on dance in metal and cultural politics in mathcore. University of Siegen PhD student Daniel Suer provided a chronological historiography of heavy music dancing, examining the connections and disagreements between four key sources. These four texts provide a narrative of ‘a short rise and very long fall’ of moshpit culture. The mainstream appropriation of moshing (e.g. at Woodstock 1999) resulted in a loss of moshpit etiquette and, echoing the emphasis of the keynote, an increase in sexual violence. Suer gave two key conclusions: the popularisation of moshing has detached the dance practice from its original codes of conduct, and the relationship between music and dance is weakening, as individuals are increasingly moshing regardless of what music is playing.

The next paper was given by Lasse Ullven, who is undertaking PhD research on Finish punk at the University of Malta. He drew upon lyrics, zines, and his original interviews to examine Finnish punk’s ‘infamous’ obsession with alcohol abuse. Without any explicit disdain for these practices, he pointed out that musicians’ deaths from alcohol-related causes are seen as a sign of authenticity and dedication. Moreover, alcohol abuse can be seen as a form of protest: it is a political act to be so drunk, so out of control, that an individual cannot be a functional part of society. By the same token, both engagement with punk and alcohol use are forms of seeking escape from social regulations. However, straight edge ethics offer an interesting counterpoint, and it is unusual that such a clear position against substance abuse emerged from punk among all music cultures.

Joe O’Connell, a lecturer at Cardiff University, closed this session with a study of canonisation in American mathcore. He examined how metal media, fans, and artists’ own branding all contribute to the formation of canons, which “serve the accumulation of capital for artists and audiences alike”. Following previous work on canonisation by Kärjä (2006) and von Appen and Doehring (2006), O’Connell argued that, through the glowing reception of Cult Leader’s debut album Lightless Walk, several critics and fans place the record in an alternative canon of mathcore. In this canon, well-respected mathcore bands such as The Dillinger Escape Plan attempt to obtain capital through a value system which prioritises musical complexity. Moreover, Converge package and re-package their cultural products (e.g. Jane Doe artwork) in ways representing mainstream canon formations – even mirroring the commercial produce of the Beatles – to “accrue economic, cultural, and/or symbolic capital”.

Day 1: Afternoon production

Following this session, the organisers provided an excellent lunch, with an admirably large spread of vegan sandwiches and finger food.

The area where lunch and coffee breaks were held featured an exhibition curated from the personal collection of DMU lecturer and PSN co-founder Alastair Gordon and designed by London College of Communication’s Russ Bestley. It was highly pertinent to be surrounded by metal and punk iconography, appropriating a university space with imagery and materials associated with heavy music cultures. (And the delegation occupying this area, mostly adorned in black and alternative fashions, must have been quite a sight for University members going about their everyday activities).

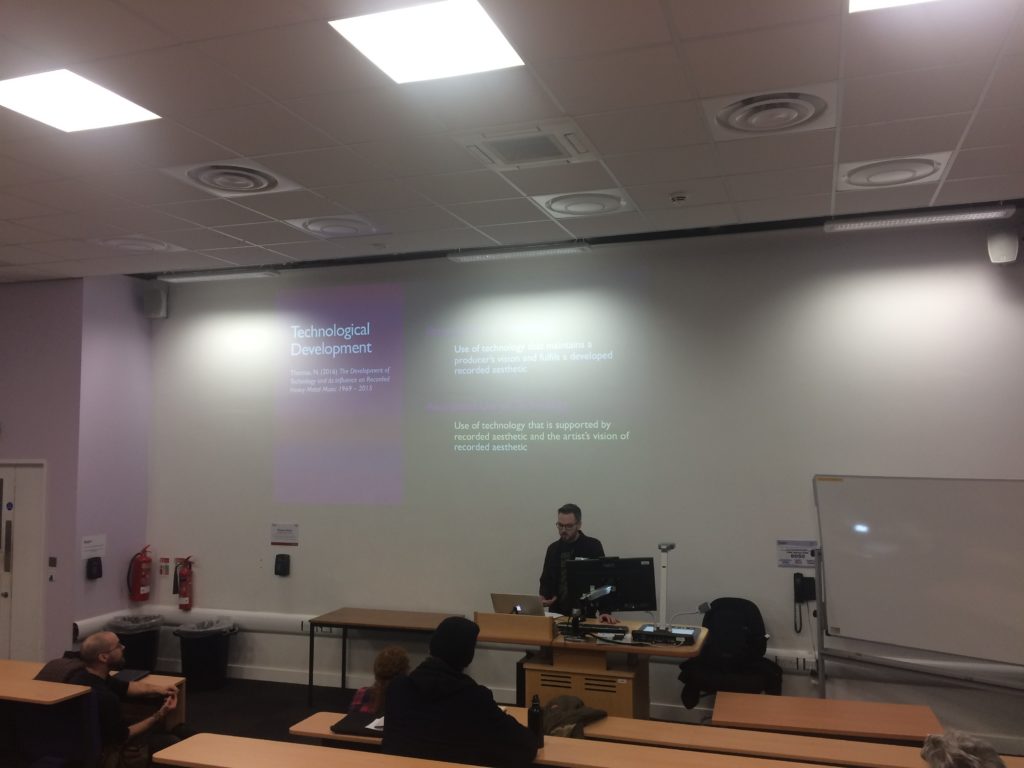

Discussing metal record production, University of Winchester lecturer Niall Thomas opened panel 2.1, on ‘The Construction and Production of Reality’. His paper examined developments in the studio production of metal music, focusing upon the varied sonic spaces that recordists create to shape listeners’ perceptions of reality. Doom metal does not conform to contemporary metal production norms, which typically prioritise hyperreality (a unique, even impossible, set of superimposed sonic spaces). Instead, doom is more nostalgic for traditional methods of record production, retaining a sense of capturing live performance in the studio. Veil of Maya’s (2017) ‘Overthrow’, by contrast, demonstrates an extreme spatial separation of sound sources in the drum kit and guitars, constructing an idealist representation of recorded music more common for modern metal production.

The following paper, by Andrew Pruitt, was titled ‘Playing in the Dirt: Crust Punk and the Irruption of the Folk’. He drew upon Baudrillard to question definitions of folk as an idealised, bucolic, pre-industrial group. This served as the basis for viewing punk as a positive assertion and performative authentication of folk identity. William Edmondes, a lecturer at Newcastle University – also known as artist Gustav Thomas or MYKL JAXN of Yeah You – concluded the panel by making a case for amateurism in creative practice. He argued that the early work of Black Sabbath demonstrates the redundancy of formally approved hierarchies in commercial popular music. The only criticism I might put to this session is that it was tricky to reorient from Thomas’ very focused paper on modern metal production to the exploratory, continental philosophy-informed perspectives of Pruitt and Edmondes.

In the next panel, Mark Perry from Oklahoma State University suggested that grunge (a ‘counter-genre’) differs from the musical conventions of metal and punk, yet pointed out more similarities with them than perhaps he realised. Daniel Makagon, formerly an A&R rep and promoter, now an associate professor in the College of Communication at DePaul University, detailed how 1990s punk bands ‘booked their own fuckin’ lives’, developing and maintaining a DIY touring network in the USA. Closing the panel, Kutztown University’s Jonathan Shaw characterised 1980s LA bands’ doom-tinged version of crossover as a response to the crack epidemic.

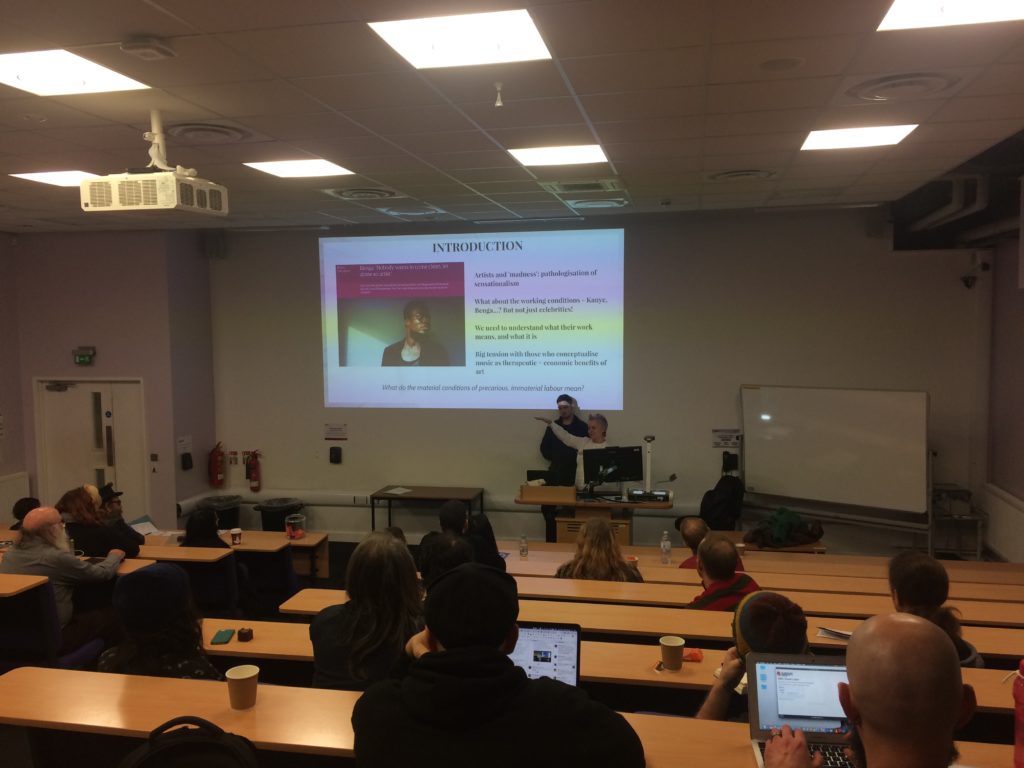

Day 1: Evening sickness and quizness

Next, Sally Anne Gross and George Musgrave (who raps as Context) gave a fantastic keynote drawing from their 2017 study, Can Music Make You Sick?. They are some of the first researchers to query wellbeing in the music industry, a topic that people are generally reluctant to discuss. In a culture of artistic creation where mental illness is pathologised, sensationalised, and/or romanticised, there is very little discourse on how careers in the industry can be damaging. Public opinion appears to hold that musicians should feel lucky to work with an art that they love for a living. Moreover, critically examining artist wellbeing stands in tension with research which conceptualises music as therapeutic, an unconditional force for good. Do check the study out for their detailed findings, which centre around musicians’ experiences of precarity in the gig economy. I am still dwelling on their impactful conclusions, well captured by two of Musgrave’s summaries: “making music is therapeutic; making a career out of music is traumatic”, and “being a musician is not an occupation, but being perpetually occupied”.

This talk was followed by a discussion between Alastair Gordon and Amy Lawson, the lead promoter at Nottingham’s Rock City. Among various personal insights, they talked about the mental health difficulties that industry personnel can experience, which acted as a firm answer to the previous talk: yes, music can make you sick!

No conference write-up would be complete without at least briefly mentioning the evening entertainment. In perhaps the least metal venue ever, Rosemary Hill masterfully presented a quiz (co-written with Kirsty Lohman) full of 80s punk/metal trivia, copious Spinal Tap references, and even a Christmas-themed singalong round. I’m still pleased to have won, with Lewis Kennedy and Niall Thomas, the prestigious prize for best team name with Triviam. (Other names we spitballed include Thin Quizzy, Quizturbed, and Quizzing In The Name Of).

Day 2: Morning experiences

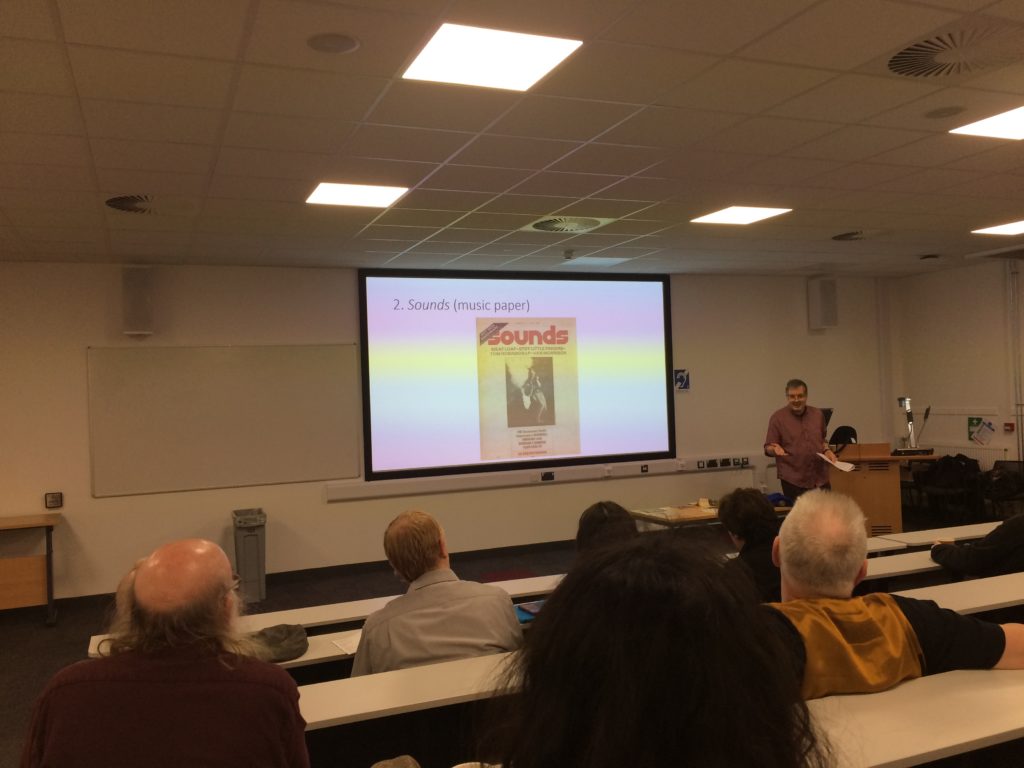

Roger Sabin, the writer of Punk Rock: So What? (1999), opened the second day of the conference with his keynote, ‘Punk and Metal in the UK, 1976–80: A story in seven objects’. He discussed – and predominantly contested – received narratives of late ‘70s punk and metal, arguing against a mediated separation between punk and metal. The personal objects he brought along demonstrated that “the crossovers are there if you look”. First, the problematic and explicitly political image of Iron Maiden’s ‘Sanctuary’ artwork [tw: misogyny, violence] challenges the established binary which upholds punk as political and metal as apathetic. Girlschool’s ‘Take It All Away’ looked like a punk record to Sabin shopping at Rough Trade in 1979, but turned out to be a metal album he enjoyed. The music paper Sounds and Deep Purple fan letter Stargazer point to the role of journalists and fans in embracing both punk and metal. A World War 2 bomb (an uneasy family heirloom), his West Ham United football club rosette, and his denim ‘battle vest’ spoke to the importance of localism as a bridge between punk and metal. Members of heavy music subcultures clung to expressions of locality, hooliganism, and the appropriation of biker culture in a society obsessed with World War Two.

In Panel 4.2, Lexi Turner admitted to ‘muddying the waters’ between punk and metal again by focusing upon goth. Drawing upon gender studies, psychoanalysis, and broader theory, Turner suggested that there is an abject/object dynamic of gothic femininity which dissolves expressions of subjectivity. Edward Avery-Natale, a sociologist from North Dakota State University, brought together Deleuze’s assemblage theory with Lauclauian language of representation. He argued that punk and metal moshpits exemplify how hegemony and discourse can be brought within assemblage theory.

My paper, ‘Transcendence in modern metal listening’, offered a theoretical framework for experiences of transcendence in metal (developed from my doctoral research) and applied it to two examples of heavy music. I suggested that a nuanced model of engagement with metal, focusing on listening experience, can provide psychological and embodied understandings of transcendence. It is important to take listeners who report such experiences seriously, and investigate beliefs and theories which may account for their responses to the music. The relationship of transcendence to transgression has significant bearings on dichotomies of the personal and the political or the nature/culture divide, and offers promising paths for further investigation.

The final paper in this panel was given by Tom Cardwell, an artist and painter who teaches at the University of the Arts London. He noted that the mainstream adoption of subcultural fashion is widely seen as a failure of authenticity, particularly among fans who are defensive about representation. Parts of high street fashion stores, such as H&M, now look like metal concert merchandise stands, displaying various adorned black t-shirts. The target audience for such clothing is surely not the original audience – H&M don’t expect metal fans to pop in to replace their Metallica t-shirt – but buyers who might not want to connect themselves with metal, indicating an extension of the symbolic place of band t-shirts into the mainstream.

Day 2: An afternoon of cultural commentaries and consistencies

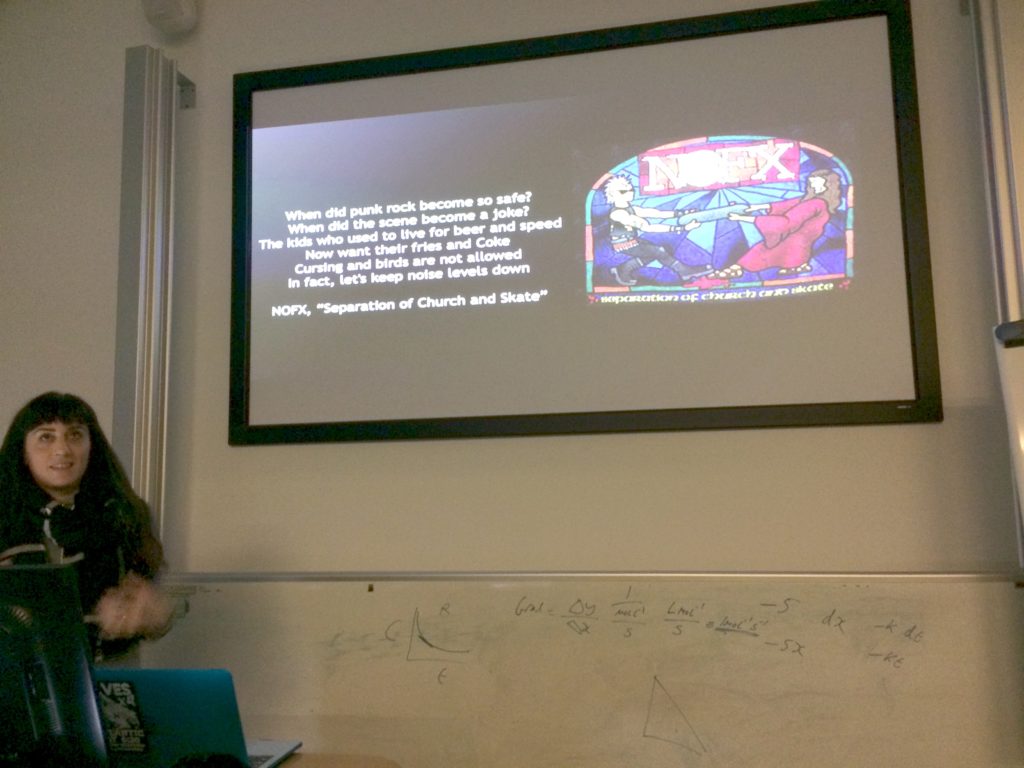

Ellen Bernhard, who teaches at Chestnut Hill College, spoke first in Panel 5.2, ‘Subcultural Theory’. Her fascinating and detailed paper focused upon the fallout from an NOFX performance where band members joked about the 2017 Las Vegas shooting (“at least they were country fans and not punk-rock fans”). As well as making US headlines, the band were dropped from sponsorships and festival slots following that incident. NOFX began to apologise on social media, opening a collective space for fans to respond. Bernhard read 2597 comments (generating a useable sample of 100 posts) to analyse how their responses provide insight into the current ethos of American punk rock. Fans suggested very strict categories of what is and what is not punk. Some saw the band’s comments as ‘punching down’, telling jokes about those who are weaker than you because they’re incapable of fighting back. Sascha Cohen (2018), by contrast, contends that the “American history of stand-up has been one of resistance and retaliation, shaped by outsider performers punching up at dominant culture”. The definition of punk is clearly complex, but the ethos surely equates to more than ‘fuck the offended’. Moreover, as a potential instance of Trump-era rhetoric, NOFX’s joke suggests how it is increasingly acceptable (for certain people, I might add) to say offensive things in public forums without repercussions.

Also in this panel, Jessica Schwartz from UCLA offered a punk poetics of the scene based around 924 Gilman Street in Berkeley. Released around the same time, Green Day’s music – highly produced pop punk – may have the veneer of DIY, but is a part of myth-making, very alienated and disenfranchised from the actual scene. In this sense, this punk scene is an example of how radical culture becomes neutralised (Hebdige 1979). Adam Loesch, who is earning a Master’s degree at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, argued that mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion are the key parts of subcultural theory. He described moving away from Birmingham (CCCS) models, neo-tribalism, and scene theory to directly address collections of inclusion and exclusion criteria for punk. From 22 90-minute interviews with 20 to 50 year olds who have been to at least three punk shows, he concluded that succeeding in a scene requires careful negotiation between physical and online spaces.

The final part of the programme was a keynote from Pippa Lang, a metal journalist-cum-punk performer who is now undertaking an autoethnographic PhD at Kingston University London. Lang’s talk neatly underscored the ongoing processes of catharsis running throughout the conference, with numerous ‘recovering punks’ trying to make sense of their adolescences in Thatcherite Britain. Among the delegates, Lang was one of the closest individuals to the frontlines of punk and metal scenes in 1980s London. She shared various personal stories and recollections, including (in her experience) the complete lack of hostilities between punk and metal scenes that newspapers so frequently reported. For Lang, working for many years at Metal Hammer, metal, rock, and punk were fairly easy to divide up until the 1990s, when grunge confused these stylistic worlds. Throughout the 1980s, metalheads and punks cohabited in the Ship pub, as “we were all at this extraordinary juncture together”. Heavy music fans experienced solidarity in both disenfranchisement and alienation from their parents’ generation, who had lived through World War Two. Hedonism was the panacea to unanswerable sociopolitical questions. In the mid-1990s, Lang found her own catharsis by playing in the punk band Disturbed UK.

Her talk, spanning academic theory and (in this case, journalistic) practice, served as an ideal closing example of the crossovers at the heart of the conference. At the conference welcome, Alastair Gordon spoke of the “hinterlands” between and around metal and punk. Yet this keynote, and many other talks over the two days, spoke to the many middle-grounds and dissolutions of boundaries between the 1970s and today. Perhaps such distinctions – although consistently maintained by certain media institutions and sites of discourse – are increasingly untenable. In this sense, participants have long been ‘doing metal, being punk, doing punk, being metal’.

References

Cohen, S. (2018) ‘A Brief History of Punch-Down Comedy’, Mask. Available at: http://www.maskmagazine.com/the-joy-issue/life/stand-up-punch-down (Accessed: 16 December 2018).

Gross, S. A. and Musgrave, G. (2017) Can Music Make You Sick? A Study into the Incidence of Musicians’ Mental Health. Winchester: University of Winchester and MusicTank.

Hebdige, D. (1979) Subculture: The Meaning of Style. London: Routledge.

Kärja, A. V. (2006) ‘A prescribed alternative mainstream: popular music and canon formation’, Popular Music, 25(1), pp. 3–19.

Kelly, L. (1988) Surviving Sexual Violence. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Sabin, R. (1999) Punk Rock: So What?: The Cultural Legacy of Punk. London: Routledge.

Veil of Maya (2017) ‘Overthrow’, False Idol. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GLu-E42-RmA (Accessed: 14 December 2018)

Vera-Gray, F. (ed.) (2016) Men’s Intrusion, Women’s Embodiment. London and New York: Routledge.

Von Appen, R. and Doehring, A. (2006) ‘Nevermind The Beatles, here’s Exile 61 and Nico: ‘The top 100 records of all time’ – a canon of pop and rock albums from a sociological and an aesthetic perspective’, Popular Music, 25(1), pp. 21–39.