For the first post on lofi hip hop before and during COVID-19, please see here.

Lofi as a genre, and its antecedents

To what extent can lofi hip hop be considered a genre, and to what extent do its producers, curators, and listeners participate in a virtual community? At present, there is a broad understanding of ‘internet lofi’ as a standalone paradigm – a distinct music style, at least – in hip hop producer communities. Emma Winston and Laurence Saywood characterise lofi hip hop as a reasonably large and stable genre (not merely a ‘microgenre’, so large is the audience) mediated online1Emma Winston and Laurence Saywood, ‘Beats to Relax/Study To: Contradiction and Paradox in Lofi Hip Hop’, IASPM Journal 9, no. 2 (24 December 2019): 40–54, 41.. Of course, genre systems are by necessity messy, a “blunt instrument” of sorts2Adam Krims, Rap Music and the Poetics of Identity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 55.. To take one approach, hip hop could be situated as a genre and lofi a subgenre thereof, although the global manifestation of all sorts of musical styles and practices under the banner of hip hop may require higher-level categorisation. It is perhaps neater to see hip hop as a metagenre3Roy Shuker, Popular Music: The Key Concepts, 4th ed. (London and New York: Routledge, 2017), 148–151, a broad-strokes designation that recognises the breadth of musical activity which still bears some resemblance to a specific origin, stylistic identity, and international diffusion. Seeing it this way, lofi hip hop can be soundly understood as a standalone genre, although it is worth mentioning that the music and its accompanying practices are disconnected from most popular music industries.

The genre has gained many listeners outside of hip hop’s usual listener base: it is, by one account, a “YouTube phenomenon [… with …] millions of devoted followers”4Luke Winkie, ‘How “Lofi Hip Hop Radio to Relax/Study to” Became a YouTube Phenomenon’, VICE, 13 July 2018, https://www.vice.com/en/article/594b3z/how-lofi-hip-hop-radio-to-relaxstudy-to-became-a-youtube-phenomenon.. YouTube is unambiguously the contemporary home of the genre, with limited spread beyond: aside from a handful of journalistic accounts and appearances on streaming services, most online traffic is directed towards YouTube as the predominant platform for consumption. Furthermore, in the context of comments on lofi mixes which discuss ‘the comment section’ as a place, notions of virtual community come to the fore. The chat boxes of live lofi channels and the comments of mixes have been described as atypically convivial and supportive spaces, in contrast to YouTube comments’ tendency towards void-yelling or endless ad hominems5Kemi Alemoru, ‘Inside YouTube’s Calming “Lofi Hip Hop Radio to Relax/Study to” Community’, Dazed, 14 June 2018, https://www.dazeddigital.com/music/article/40366/1/youtube-lo-fi-hip-hop-study-relax-24-7-livestream-scene.. What happens to this space when listeners find themselves under the quarantine conditions of COVID-19? My focus here, on changes in listener commentary, offers some useful insights regarding the state of lofi as a genre and as a community, with manifest effects on how listeners self-identify in relation to the music.

Though a full genre history or even a folksonomy is far beyond the scope of this post, there are evidently complex links between earlier internet genres, other music described as lo-fi (with hyphen), and lofi hip hop. This modern manifestation of lofi, though musically quite distinct, can be traced back to certain genre conventions developed through hypnagogic pop, chillwave, and vaporwave. These are all, in a manner of speaking, genres enabled by YouTube’s quick content sharing and discovery facilities, and their aesthetic tendencies have emerged and dissipated in complex patterns. Hypnagogic pop is received as evoking “the state between sleep and wakefulness”6Georgina Born and Christopher Haworth, ‘From Microsound to Vaporwave: Internet-Mediated Musics, Online Methods, and Genre’, Music and Letters 98, no. 4 (2017): 601–47, https://doi.org/10.1093/ml/gcx095, 629., drawing on a romanticised and highly imaginary past characterised by ‘80s U.S. popular culture, especially consumerist rhetoric epitomised by cassette tapes. Aside from the amateur tape labels at the heart of hypnagogic pop, however, the genre in large part gave way to chillwave and vaporwave, both of which became better-known in mainstream digital culture and gained larger audiences, especially on YouTube.

Georgina Born and Christopher Haworth describe chillwave (the digital-native genre par excellence) essentially as hypnagogic pop with less experimentation and a sharper focus on conventional pop song structure. Its identity on YouTube is formed around retrofuturistic references to ’80s electronic dance music and video games, especially arcade racing games like Pole Position (borrowing the visual imagery and rhythmic consistency of driving). Vaporwave is often taken to be more actively ironic and politically engaged, serving as a critique of consumer capitalism and the failures of economic models emphasising constant growth. As Laura Glitsos has explored7Laura Glitsos, ‘Vaporwave, or Music Optimised for Abandoned Malls’, Popular Music 37, no. 1 (January 2018): 100–118, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143017000599., the disused shopping mall is an emblematic image for vaporwave aesthetics, tying together disdain for – and interest in the strangeness of – 1990s corporate marketing, the computerisation of office labour, muzak®, and the false future once promised by rapidly evolving technology markets like Japan.

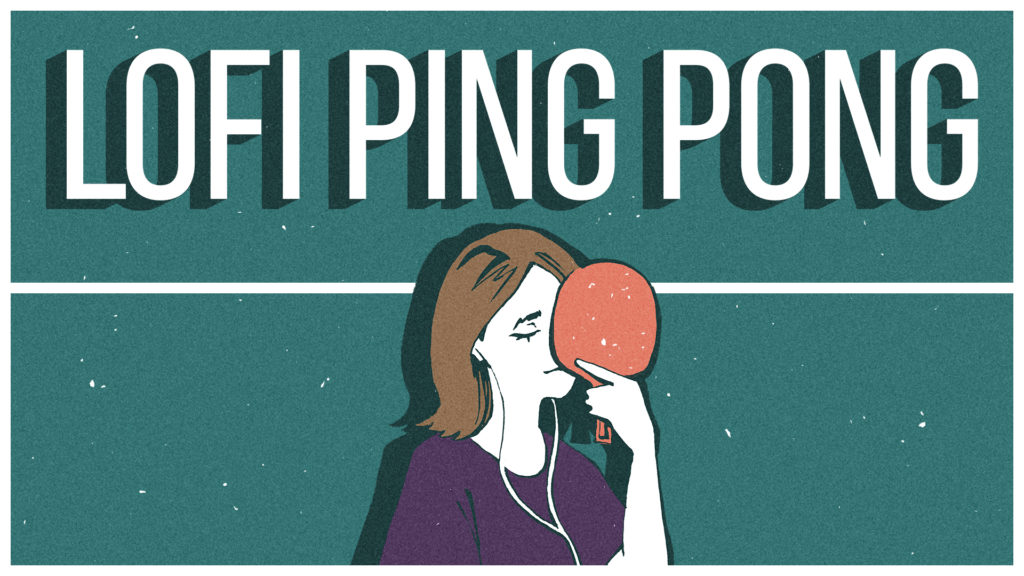

To an extent, each of these genres has something lofi about them, not least their embrace of audio imperfections and disintermediation from the mainstream music industry. Indeed, Adam Harper’s 2014 doctorate traces ‘lo(-)fi’ as a term and an aesthetics of popular music production all the way up to the sounds and styles of lofi hip hop8Adam Harper, ‘Lo-Fi Aesthetics in Popular Music Discourse’ (DPhil Thesis in Musicology, Oxford, University of Oxford, 2014).. Although now only loosely connected to other meanings in the history of ‘low-fidelity’, it is striking how well-known lofi hip-hop, the contemporary flag-bearer for the term, has become across the social web and in youth culture. Consider, for one example, its appropriation in the rhythm game ‘lofi ping pong’, as Harper recently highlighted9Adam Harper, ‘What Is Lo-Fi? A Genealogy of a Recurrent Term in the Aesthetics of Popular Music Production’ (Research Seminar, City University London, 9 December 2020).. This transferral to other media indicates that the genre is associated with a reasonably stable set of aesthetic conventions (such as the sad/pensive young woman, pastel colouring, and visual artefacts – paint chips? – in the game artwork). But what exactly are the themes that characterise lofi hip hop as a genre, and how are these manifested in YouTube commentary – the genre’s primary discursive arena – before and during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Witches and ghosts

There is much to be said about the expression of personal identity in the lofi community, although little demographic data exists besides the informed impressions of Winston and Saywood10Winston and Saywood, ‘Beats to Relax/Study To’, 41., who assume the typical commenter to be a school or university student. I would add that the audience is likely to be in large part North American or European, given the concentration of producers and curators in these areas. Of those whose gender can be assumed by commenter name, my data shows a roughly even split between male and female participants, although this is not by any means a firm finding given the methodological issues here (as I outline in commentary on ‘WAP’). In any case, besides traditional social demographics, there are interesting new associations and personal identifications which have emerged during the pandemic.

The most statistically significant terms in the entire sample are “witch” and “ghost”. Related terms include “witches”, “witchcraft”, “wizard”, “spell”, “warlock”, and “wiccan”. First, a simple explanation: two of the most commented-on lofi mixes of 2020 are Homework Radio’s “Lo-fi for Ghosts (Only)”, uploaded in August 2019, and “Lo-fi for Witches (Only) [lofi / calm / chill beats]”, which went live on 27 March 2020. Naturally, there are few references to witches and ghosts prior to 2020, and the many participants responding to the video titles make use of these terms significantly more often in the during-pandemic sample11Even though the mix mentioning “ghost” was live for nine months before the cutoff date, the word appears at least twice as often since March. Furthermore, since both videos are on the same channel, the success of “Lo-fi for Witches” may have … Jump to footnote. This alone makes for a relatively uninteresting finding: there’s a new video and commenters mention its title. However, the mystical imagery and fantastical identities invoked by these mixes during the COVID-19 pandemic – and picked up on by the audience – are worth some consideration.

What does it mean to feel like a ghost or a witch? Certainly, lofi listeners identify more closely with these figures of late. Loneliness and social isolation are the topics of numerous research articles which have have examined the impacts of quarantines and lockdown measures12Yuval Palgi et al., ‘The Loneliness Pandemic: Loneliness and Other Concomitants of Depression, Anxiety and Their Comorbidity during the COVID-19 Outbreak’, Journal of Affective Disorders 275 (1 October 2020): 109–11, … Jump to footnote. Indeed, one technical term used often in public health advice is ‘self-isolation’, which encourages staying at home (sometimes ‘shelter in place’) as responsible behaviour for most citizens13This is not lost on Dazed journalist Sophie Atkinson, who describes lofi girl as “the poster girl for responsible coronavirus behaviour for Gen Z and millennials alike”. See Sophie Atkinson, ‘The “24/7 Lo-Fi Hip Hop Beats” Girl Is Our … Jump to footnote. The practical consequences of self-isolation align closely with the emotionally isolated imagery of ghosts and witches. For example, experiences of staying indoors (perhaps against one’s will), seeing less sunlight, feeling invisible or unable to engage with others, and having more time to dedicate to (potentially esoteric) hobbies may cause positive identification with these supernatural figures, who are excluded from a regularly functioning society. As for the other terms which appear in much higher proportions, such as “wizard” and “warlock”, these are also responses to the video titles, mostly asking questions to the effect of “what about lofi for wizards?”.

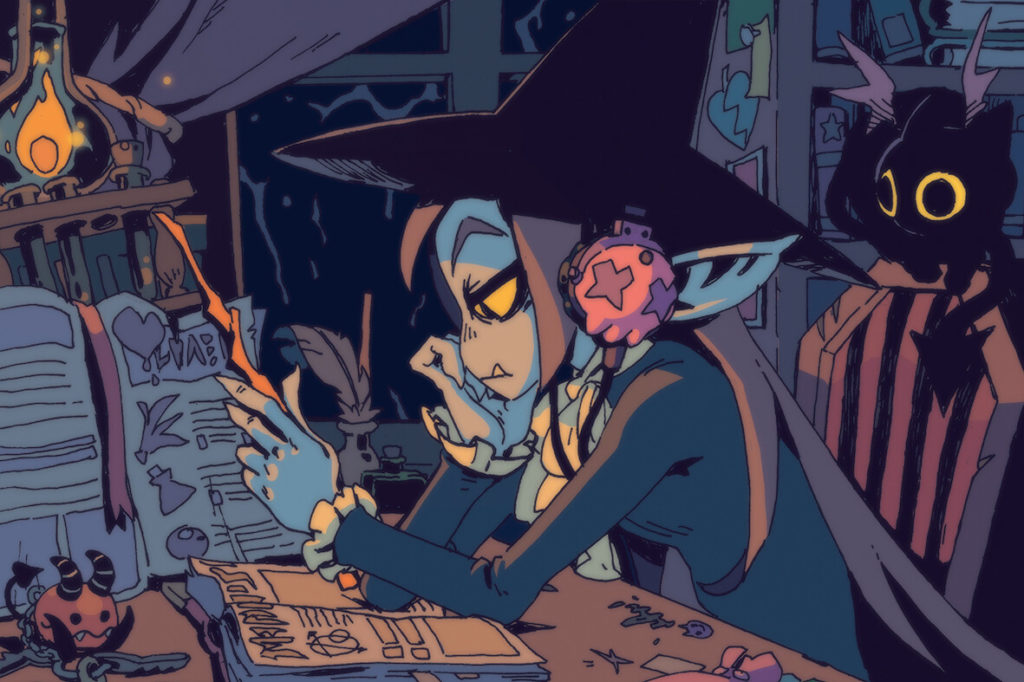

Somewhat more speculatively, the witch figure and its accompanying “witchcraft”, “spell”, and “wiccan” may have struck a chord with the lofi audience due to teenage-oriented associations between studying and magic (as popularised by the Harry Potter universe, for one example). The significant rise in studying to lofi while spending more time inside and socially disconnected makes the witch an engaging figure, especially playing on pop cultural tropes of the witch as a teen hero. Studiousness and natural magical power have gained close associations through characters like Hermione and Willow from Buffy the Vampire Slayer, which the video of “Lo-fi for Witches” draws upon through visual references. It replaces ChilledCow’s ‘lofi girl’ figure with a cartoon witch leant over a desk, complete with pointed hat, open spellbooks, wooden wand, black cat (itself boasting demonic wings and tail), vials, inks, a quill, and – perhaps anachronistically – skull-shaped pink headphones resting on her fantasy-/anime-inspired pointy ears. Naturally, as students keep going under lockdown conditions, confined to bedrooms and dorm rooms in self-isolation, the image of a lonely witch working hard on their arcane craft feels increasingly relatable. A handful of commenters asked the community for a spell to help them pass upcoming exams.

The references to witches also appear to have invited commentary from those interested in neopaganism, hence “wiccan” emerging as a term used in this space. Popular interest in mystical practices appears to have increased over the last few years, as evidenced by participants in communities like WitchTok14Lauren McCarthy, ‘Inside #WitchTok, Where Witches of TikTok Go Viral’, Nylon, accessed 11 January 2021, https://www.nylon.com/life/witchtok-witches-of-tiktok.. There may be overlap between contemporary witchcraft and a reemergence of anti-science rhetoric associated with, for instance, COVID-19 conspiracy theories. The connotations of alternative medicine and New Age thought more broadly are troubling given the infodemic precipitated by the disease15Matteo Cinelli et al., ‘The COVID-19 Social Media Infodemic’, Scientific Reports 10, no. 1 (6 October 2020): 16598, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73510-5., although most comments here are pretty innocuous. On the whole, witches (and ghosts) appear to capture something distinct about the lofi audience’s experience of social isolation, circumstances undoubtedly intensified by the pandemic. Almost all of the discussion in this section comes from the “witches” video, so there is also the general observation to be made that mix titles and visuals can strongly sway the topic of commentary, even when the music is relatively indistinct from other lofi mixes. Homework Radio’s comparable attempts at producing lofi for “vampires”, “space cowboys”, “demons”, “mermaids”, “angels”, “grim reapers”, “cats”, and “insomniacs” have not (yet) proved quite as successful. The pop-cultural imagery of witches and ghosts evidently fit a particular niche that aligns with lofi’s aesthetic themes and the specific circumstances of COVID-19.

aesthetic

There are broader aesthetic tendencies that form part of the genre’s identity: a prominent example is this kind of typing , which has been recognisable as a feature of lofi discourse since at least 2015. Known as ‘aesthetic’ text or more reductively ‘the vaporwave font’, typing with fullwidth characters (or simply placing a space between each letter) is a hallmark of lofi hip hop comment sections. This use of vaporwave’s earlier stylistic signifiers – perhaps by way of capital letters and hanzi/kanji – is inherited fairly directly, and so the text finds its way into many lofi mix titles and comments16For example, tracks now considered to be vaporwave classics, from albums like フローラルの専門店 (‘Floral Shoppe’) by Macintosh Plus and FINAL TEARS by INTERNET CLUB, are commonly rendered in capitals and include Chinese and Japanese … Jump to footnote. The common letters “c”, “d”, “e”, “g”, “h”, “k”, “m”, “n”, “o”, “p”, “r”, “s”, “t” (which are processed by Mozdeh as independent words, and thus revealed in the sample) appear frequently within such texts. However, the statistical significance shows them in a much greater proportion of comments written prior to March than those posted during the pandemic. Put simply, individually spaced letters have been used less often recently: this kind of typing, once a key lofi signifier, appears to be going out of style.

There are many reasons why this could be the case. A straightforward explanation is that the COVID-19 pandemic and the genre’s rising popularity over time has brought many new listeners to the YouTube mixes17Julia Alexander provides various pieces of evidence for an increase in viewership correlated with COVID-19 lockdown measures. See Julia Alexander, ‘Lo-Fi Beats to Quarantine to Are Booming on YouTube’, The Verge, 20 April 2020, … Jump to footnote, who have posted using normal typography. While the aesthetic text tradition carries on today (and is not necessarily less meaningful for the genre’s participants), it was simply present in a greater proportion of comments before March 2020, as the arrival of new users has skewed the sample towards conventional text. Whether newcomers observed the typing trend and chose not to emulate it or are yet to encounter it altogether is unclear. However, the style might be seen as somewhat tired by now, mostly dissolved into meme fodder (as museumised by the Know Your Meme page). Across the web, the typing style might be interpreted pejoratively as a symbol for a subculture of over-sentimental digital natives with nostalgic feelings18I write this in reference to the single-word titles of two popular lofi mixes: “NOSTALGIC” (15 million views), uploaded by Neotic, and “Feelings” (11 million views) by Cabvno. Note that both were published … Jump to footnote.

Cultural references

Indeed, nostalgia is a central theme of Winston and Saywood’s study of lofi hip hop, as they observe the genre activating “hyper-specific memories of popular media which may have been consumed during, or at least associated with, a listener’s childhood”19Winston and Saywood, ‘Beats to Relax/Study To’, 41.. However, it appears that a recent emphasis on new topics – not only witches and ghosts but also COVID-19 measures, studying, etc. – has led to a significant decrease in pop-cultural references typical of the genre. Mentions of the animated TV series Cowboy Bebop (“bebop”) and Rick and Morty (“morty”) appear much more often prior to March 2020. On the one hand, this might be surprising, as viewership of popular TV shows surged during lockdown conditions20BBC News, ‘TV Watching and Online Streaming Surge during Lockdown’, 5 August 2020, sec. Entertainment & Arts, https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-53637305., and we could expect to see an associated spike in commentary on them. On the other hand, this indicates the declining popularity of mixes using visual imagery and audio samples from cartoons. For instance, the 2016 mix “Chill Study Beats 2 • Instrumental & Jazz Hip Hop Music [2016]” opens with spoken audio extracted from Cowboy Bebop, which listeners frequently identify. In 2017, Cabvno posted Feelings, featuring a short video loop of Morty (plus superimposed VHS tape effects) which also appears as the video thumbnail.

Fewer visual references appear in recently uploaded lofi mixes. Evidently, the more generic imagery of witches have drawn a lot of attention away from specific TV shows, but there might also be a stylistic change present in lofi hip hop, with fewer samples of popular media used across the board.

Indeed, a 2017–18 series of ‘Volumes’ by the bootleg boy has an aesthetic identity strongly informed by specific cartoon characters. A still image or short animated loop of the character (usually crying) is accompanied by audio samples from the associated series, especially extracts of emotional dialogue. For instance, in the thirty seconds opening “BAD FEELINGS”, a video of Bart Simpson crying is complemented by audio from The Simpsons drenched in reverb (ostensibly to seem more dramatic and significant). Marge asks Lisa to repress her emotions: “take all your bad feelings, and push them down…”. After a pause, Lisa responds “but I don’t feel like smiling”, and this resolution to embrace her negative emotional state continues echoing as the beat drops with the entry of drums and bass. Bart carries on spilling a tear every second in the video. Instances like this exemplify both referential and nostalgic qualities of lofi, which appear less common in recent months (for instance, “simpson” appears at least twice as often prior to March 2020). The cultural spread – at least of the meme status of the lofi mix title format – became evident when the BoJack Horseman episode “Sunk Cost and All That” mentioned lofi. the bootleg boy uploaded a BoJack Horseman ‘volume’ in August 2018, but this is the first time a TV show referenced lofi back so explicitly21Prior to this, The Steven Universe character Connie has been depicted emulating the ‘lofi girl’ artwork. See this image hosted on KnowYourMeme..

However, a couple of new connections have appeared. No significant lofi ping pong mentions in my sample of comments (yet?), but many listeners have revealed that they were linked to a specific lofi mix by the 2020 interactive detective game “Duskwood”. As for other games, older videos using generic and thematic imagery can gain relevance down the line. For instance, several commenters took to the 2018 mix “Samurai ☯ Japanese Lofi HipHop Mix” to mention the game Ghost of Tsushima (with a significant proportion of recent “tsushima” references), which was released in July 2020. Leaving the broadly stereotypical and Orientalist framing to one side, the game and the ‘Japanese’-inspired mix appear to be mutually enhancing for players and listeners. One commenter (paraphrased, but all significant words retained) reflects that:

“This mix feels like when I’m playing Ghost of Tsushima just riding through the sunny fields past all the flowers”

Mentions of the mix visuals have increased recently, with the terms “balcony”, “cat”, and “typing” referencing specific imagery used in the video content (“1 A.M Study Session” for the first two, “aesthetic song” for the typing animation). The increase in uses of “she” partially owes to the widespread commenting on the visuals of ‘lofi girl’, as in artwork by Juan Pablo Machado or Margaux Peltat, but also appears in a lot of posts about interpersonal relationships with female people (e.g., “I miss my girlfriend, she used to cheer me up”). However, references to “clock” appear significantly more often in the earlier sample, usually noting the static time reading displayed on the digital clock in “3:30am”. This 30-minute mix displays (you guessed it) ‘03:30’ for the entire duration, and the flashing pink light illuminating the clock face is the only animated part of the video. It surely draws attention to a sense of frozen time, although users commonly used to poke fun at the clock (either its disparity with the analogue star-shaped clock also depicted in the video or the YouTube scrub bar, conspicuously keeping track of seconds as the mix progresses). Maybe this video is simply less popular, or the joke might just be tired.

Musical references

References to music have reduced substantially during COVID-19, save for one term which I’ll reveal in a moment (the suspense!). In the years prior to the pandemic, hundreds of commenters recognised a popular lofi beat, “Waves” by Freddie Joachim, and pointed out that it was used by Joey Bada$$ (“Waves”) and later J. Cole (“False Prophets”). This is much less common now, likely indicating a natural decline over time rather than any significant relation to COVID-19: a few years have passed since the rap tracks were released. Music is discussed more generally using the terms “mix”, “genre”, “vaporwave”, “chillhop”, “music”, “beat”, “where”, and “track”. All of these show statistically significant decreases since March 2020, as people are generally commenting on the music of the videos less often. What occupies their thoughts instead, one would assume, are the other terms discussed throughout this blog post (especially part one’s focus on COVID-19 and studying).

The term “mix”, once a staple for referring to any video featuring twenty or so lofi tracks, has dramatically fallen out of use (present in 1.99% and 0.98% of comments before and after March 2020 respectively). Use of this term is generally pretty simple, like “this is my favourite mix”. “Music”, “beat”, “where”, and “track” have similar applications, as listeners either discuss the music or attempt to locate pieces in different contexts. “Genre” is a more interesting decrease, because a few years ago it was much more common for people to ask questions like “what is this genre called?”. And 161 commenters gave the (erroneous?) answer “vaporwave”, which has dropped to only 10 mentions since March 2020. One user suggests that the term ‘vaporwave’ may have originated from “a group of guys who vape a lot”. Those inaccuracies aside, a couple of the lofi mixes do feature some tracks that might be better labelled vaporwave (e.g. “NOSTALGIC”), especially before the genres were more separately codified. Further pointing to the complexities of the genre network active in this space, posters were much more likely to use the term “chillhop” between 2016 and early 2020 than in recent months. This decline might also give some indication that the uploaded mixes (but not necessarily the live-streams) of the channel Chillhop Music have decreased in popularity.

The largest upswing in music-related terminology – here’s the big reveal – appears for the word (the one, the only) “lofi”. Clearly, the genre has coalesced around this label, being the only referential word that has become much more frequent in the sample of texts since major COVID-19 pandemic measures were put in place. Like many of the terms in this section, I doubt this change has any significant relationship to the coronavirus itself. Much more likely is that we are observing changes in the life of lofi hip hop as a genre, as discourse shifts in response to codifications and crystallisations of the music and the digital spaces it occupies. Slightly further down the list, still highly significant (p≤0.001) although beyond my cutoff for extreme significance, the terms “hop” and “hip” appear (in that order) as more popular in the earlier subset of the sample. So without the additional clarifications of “hip hop” and “beat(s)”, as well as “chillhop” and “mix”, the standalone genre label “lofi” is in and, presumably, here to stay. Users confidently use the term to refer categorically to ‘curated lofi hip hop mixes on YouTube’:

“Lofi is awesome. I listen to it everyday from 1pm to 10pm”

“I’m super high right now and I’m telling you this is the best lofi to listen to when you’re faded”

“The world would be ten times better if everyone listened to lofi”

“I feel so chill when lofi is on”

“Thank you for helping me study with the relaxing lofi”

“I love laying in bed with some lofi and just thinking about everything”

It therefore appears that, at present, lofi can be confidently pinned as a standalone genre. This is not an effect of COVID-19 per se, although shifts in the online audience precipitated by the pandemic conditions might indicate clearer definitions of its aesthetics, boundaries, and conventions (even as they remain in flux).

Topics of conversation: appraisal, conversation, memes

There has been less use of a number of related terms, which I have thematically clustered around appraisal of the music: “love”, “dope”, “good”, “first”, and “beautiful”. Why might these appear less often during COVID-19? The vast increase in terms like “safe” offer one explanation, as commenters are focusing on more fundamental needs, like ideas of security, and are therefore distracted from aesthetic appreciation. To read a little further, the less frequent appearances of “dope” are understandable given the similar drop-off in references to “hip hop”. With its origin in hip-hop slang, the term (like reference to the metagenre and related tracks by Joey Bada$$ and J. Cole) tails off over time into the contemporary context of (just) “lofi”. This development may suggest an influx of listeners from outside the typical cultural spaces of hip-hop, as the genre is further distanced from its origins in instrumental hip-hop production (Nujabes, J Dilla, Madlib) and establishes new aesthetics inspired by anime22This observation does not mean to downplay the solid ties between other forms of hip-hop and anime. and other popular animated TV shows, studying, creative hobbies, and cosy bedroom comforts.

Alongside the decrease of inquiries about the genre name, fewer listeners are asking about or evaluating the “first” track of a mix, which is typically how this word is deployed. The reduction in the frequency of “love” is more surprising (to me, at least), given how prominently it appears in general: it is used in 8.4% of comments prior to March 2020, and 6.8% after. The lofi audience is highly expressive about their appreciation for the mixes, other commenters, and the wider community itself. Not only is lofi more widely understood as a genre on its own terms, but listeners are increasingly recognising the presence of a lofi community, complete with specific values, priorities, and normative practices. It may come as no surprise that uses of the term “community” have significantly increased in recent months. Julia Alexander reports that

YouTube’s lo-fi hip-hop community has for years offered a place to virtually gather, do homework, and find comfort in the random messages of strangers that populate in live chats. Now, as we’re all stuck inside due to the pandemic, those streams have become more popular than ever — not just as background music, but as ways to find community in a difficult time.23Alexander, ‘Lo-Fi Beats to Quarantine to Are Booming on YouTube’.

As it grows, this virtual community has become increasingly conversational, as indicated by the terms “hi” and “comment”. The common greeting appears in many comments that are direct replies to other individuals, but also quite commonly to an assumed audience (“hi, everyone”). Commenters greet other listeners as (a substitute for) social interaction and, I might suggest, a momentary statement of ontological security. This hailing of a virtual community or imagined other, sometimes posed as “whoever ends up reading this comment”, may help users gain feelings of “security in the sense of self and confidence in the continuity of one’s being-in-the-world”24Lynn Jamieson, ‘Personal Relationships, Intimacy and the Self in a Mediated and Global Digital Age’, in Digital Sociology: Critical Perspectives, ed. Kate Orton-Johnson and Nick Prior (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2013), 13–33, … Jump to footnote. Indeed, lofi mix comment sections appear to have become important outlets for coping with loneliness experienced during COVID-19. Frequently, commenters will offer advice to the crowd:

“hi everybody. make sure to drink enough water and regular meals today”

“Hi to everyone studying for exams, we’ll get through this, keep going!”.

Despite the increase in introductory terms like “hi”, the lengthy personal reflections typical of lofi commentary seem to be dwindling somewhat. There is a clear reduction in the use of the common sentence words “I”, “of”, “what”, “up”, “these”, “in”, “it”, “the”, “about”, and “this”. It seems likely that, instead of quite so many lengthy comments diarising individual feelings and events, users are more often greeting each other and partaking in newer trends of the comment section. The term “vibing” is extremely significant here, which I see as a conversational term due to the notable presence of comments like “who’s still vibing to this in 2020?”. This desire to share an activity with others further affirms a sense of communality united by common behaviours. One user gained two thousand likes on a post detailing an apparently relatable scenario:

“anyone else vibing to this in bed in a hoodie waiting for the coast to be clear at 2am to go grab some cereal?”

There is a vivid image here – a young person who lives in their parental home and with a private bedroom (or perhaps a dorm in a shared halls of residence) listening to lofi in the early hours using a personal laptop or smartphone and awaiting a quiet time when others in the house are asleep so that they can sneak to a shared kitchen for a late night snack – with which thousands of lofi listeners connect.

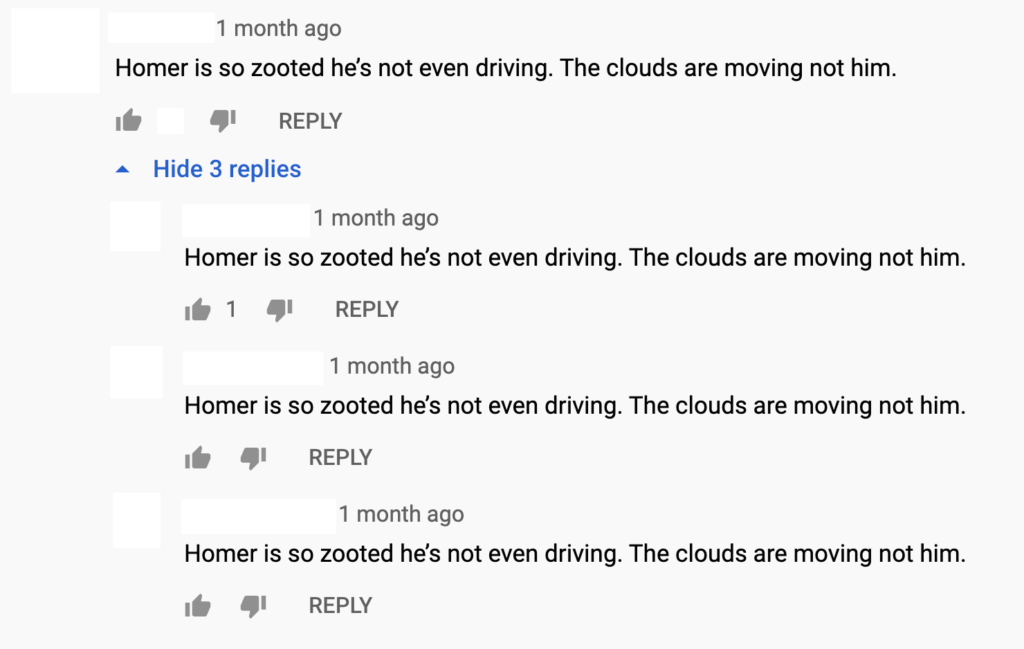

Not only are certain listening habits shared by many users, but lofi also boasts a series of popular in-jokes. In this context, by ‘memes’, I am basically referring to text-based humour. I borrow the term from web culture because this is how users would likely address these highly repetitive and formulaic comedic posts. Notably, the popularity of these memes is on the rise. The terms “zooted”, “homer”, “plot”, “pov”, “twist”, “copying”, and “copied” are much more frequently used after March 2020. There is one video where these memes run rampant, although variations on them do appear elsewhere: this GEMN video, featuring an oversaturated video loop of Homer Simpson (yes, another appearance of The Simpsons: the cartoon nostalgia runs deep) with heavy eyelids, nodding his head from side to side while driving as clouds pass him by. This animation has ‘stoned’ affordances of spaced-out relaxation and an altered sense of time, as though under the psychoactive effects of cannabis. The visuals have provoked users (and, likely, bots) to repeatedly post the phrase:

This spam/copypasta meme appears so many times that repetition and ubiquity become part of the joke itself. Out-of-the-loop visitors to the comment section can be struck by the uncanny omnipresence of this text string as they scroll down. Later, commenters vary on the theme:

“POV: You’re looking for a comment that says “Homer is so zooted he’s not even driving. The clouds are moving not him.””

This repeats at increasingly meta levels:

“POV: you’re looking for a comment that doesn’t say “POV: you’re looking […] “Homer is so zooted […]”””.

The “plot twist” format works similarly to “POV”, asking the reader to imagine the scenario which follows, typically as a form of subversive humour (as in “plot twist: she [lofi girl] is actually right handed and has just been practicing writing with her left all this time”). These simple comedic expressions manifest as small exercises in community recognition and bonding, as commenters come up with their own “plot twists” and engagements with the ongoing in-jokes. The increasing popularity of such memes may again indicate the arrival of a larger audience less familiar with lofi conventions. This would account for the “major bump in viewership” witnessed by lofi channels during March and April 202025Alexander, ‘Lo-Fi Beats to Quarantine to Are Booming on YouTube’.. As mixes have gained larger audiences, users’ tendencies have, on average, shifted towards generic web-culture meme spam and away from older staples of lofi commentary like personal reflection.

Emotional expression

Emotionally sincere commentary has been a hallmark of lofi mixes since their earliest days on YouTube, with connections to Tumblr’s conventional mode of discourse. Winston and Saywood write of the “emotional narrative microfiction” that characterises much lofi commentary, which they observe in relation to “affective labour”26Winston and Saywood, ‘Beats to Relax/Study To’, 47–48.. While this was evidently a mainstay just a few years ago (Winston and Saywood mostly quote posts from 2017), numerous words relating to personal feelings have appeared less commonly since around the time that COVID-19 measures were enacted. These include, in rough order by statistical significance, “life”, “feel” and “make” (often in the phrase “makes me feel”), “alone”, “depressed”, “feeling”, “nostalgic”, “out” (e.g., “get all my feelings out”), “sad”, “childhood”, “everything” (usually to mean overwhelming feelings), “mind”, “nostalgia”, “depression”, and “lonely”. The only emotional term that has significantly increased in use is “safe”, which is understandable given the near-global public health messaging around safety (see also part one)27Note that “safe” frequently appears in the idiom “stay safe”, which may not be as emotionally charged as, say, “depressed”..

What should we make of the reduction in the use of so many emotional terms? Like many other words discussed here, there is undoubtedly a sense that more diverse commentary from outsiders and newcomers to the lofi comment sections has increased the general ‘noise’, enabling us to see a reduction in marked terms. It might also be the case that the emotional expression that used to accompany lofi mixes so popularly has runs its course, as users are finding different outlets for discussing their feelings. More speculatively, I wonder whether COVID-19 messaging has resulted in inhibited commentary on emotions – a sort of ‘stiff upper lip’ attitude – where listeners are attempting to demonstrate resilience in the face of the grave circumstances, and therefore less often detail how they feel in the comments. In any case, this is an interesting finding given that one would expect the pandemic to have prompted discussions of loneliness, even where commenters report positive connections, like

“im in quarantine and yall make me feel less alone”.

In line with the reduction in emotional language, there has been less recourse to ‘explicit’ language since March 2020: “shit”, “fuck”, and “fucking” all see a significant drop in usage. While “fuck” is usually employed as an expletive (rarely with sexual connotations), “shit” does not always have an intensifying function. “I’m such a piece of shit” certainly carries an intense, negative emphasis, but the term is more commonly used as a generic sentence object, as in “stuff”, e.g.:

“listening to this shit makes me feel alright”

It may come as a surprise that lofi commenters use less emphatic language in recent months, but it perhaps suggests endeavours to stay calm during extraordinary events. I am reminded of popular discourse accompanying the first lockdown in the UK, where there was an impression of an emotional shift over time as early anxieties turned to humdrum boredom: one study of Google Trends data (albeit pre-peer-review) over this period shows a substantial and sustained increase in web searches relating to boredom28Abel Brodeur et al., ‘Assessing the Impact of the Coronavirus Lockdown on Unhappiness, Loneliness, and Boredom Using Google Trends’, ArXiv:2004.12129 [Physics], 25 April 2020, http://arxiv.org/abs/2004.12129.. However, it is also possible that lofi “to relax to” plays an increasingly important part in the reduction of emotionally extreme words. The more moderate language used by lofi commenters since the start of the pandemic may suggest that the “supportive elements of the chatroom and the calming effects of the music” are working29Alemoru, ‘Inside YouTube’s Calming “Lofi Hip Hop Radio to Relax/Study to” Community’.!

Conclusion

The findings discussed in part one reveal a variety of responses to COVID-19 in lofi hip-hop commentary. Users described their current circumstances, with two particularly common scenarios: listening in lockdown or quarantine and having lofi music on while completing study or homework. Such contexts were capitalised upon by new mixes promoted to an audience of “witches” and “ghosts”, figures that appeared particularly relatable given the social isolation of lofi listeners during the pandemic. The other themes addressed in this blog post, however, have much less to do with direct impacts of COVID-19 and much more about developments in the genre’s norms and its changing audience between 2016 and 2020. These are more ‘natural’ shifts over time, I would argue, and may be comparable to the chronological evolutions of other genres.

The genre itself has thoroughly stabilised around the term “lofi” (with other terms falling out of favour) at the same time that conventional practices have diversified (for instance, less frequent use of signifiers like aesthetic text). New notions of identity have been prompted by video titles and artwork, and memes specific to the comment sections have become more proportionally represented. Popular media (especially cartoons) which evoke nostalgia in listeners are referenced less often, whereas the video imagery of lofi mixes themselves are discussed more frequently. On the whole, we see less frequent emotional expression, as fewer users are taking to the comment section as a place to share and process their feelings (with the notable exception of “safe”, no doubt influenced by COVID-19 public health messaging). In general, people wrote fewer full sentences than before the pandemic, and employed less ‘explicit’ language implying intense feelings. There is less negative emotional reflection as lofi’s large student listener base is, it seems, productively diving into their studies (that is, they appear to feel better now they’re working harder: how’s that for a neoliberal takeaway?).

Taken together, these developments suggest an influx of first-time viewers adjusting to (and thereby altering) the conventions of lofi commentary. Notions of community are strengthened as a new audience arrives during the strange, troubling, and often lonely circumstances of COVID-19. Individuals in this expanding listener base often introduce themselves in comments, and appear to be welcomed by others. In many cases, this introduction takes the form of participating in copypasta threads, a relatively novel feature of lofi commentary (inherited from other meme activity across the social web). The introduction of new elements might appear to be a threat to “one of the kindest communities on the internet”30Alemoru, ‘Inside YouTube’s Calming “Lofi Hip Hop Radio to Relax/Study to” Community’., but there does not seem to be much outgroup resentment, hipsterism, or gatekeeping, as far as my sample shows.

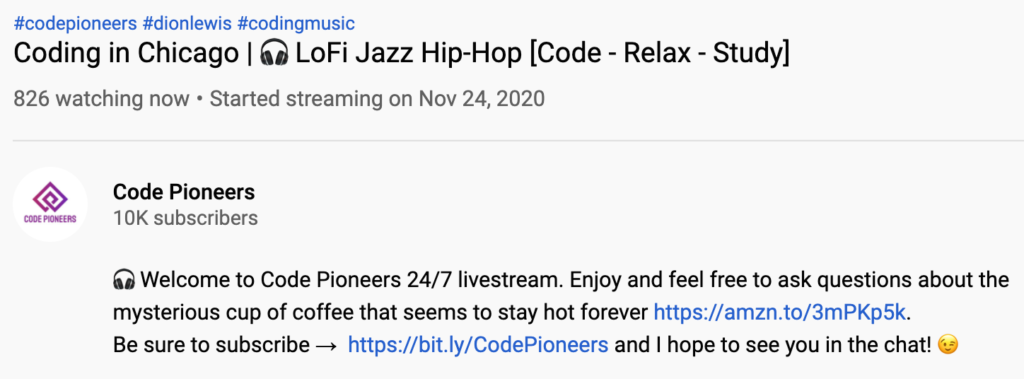

There is much more to say here, not least because some of the most popular lofi resources are now live-streamed ‘radio channels’ with a real-time chat function. Mix videos and comments may be revealing earlier trends in discourse that do not fully represent lofi in its most recent manifestation, as the community increasingly embraces live videos with accompanying chatrooms. The critical scholar in me is most troubled by commercial adoptions of the trend (a death knell for an internet subculture if ever there was one): in part one, I mentioned Will Smith’s merchandise sales mix, but there is also The AMP Channel (developer community)’s “code-fi”, Joma Tech (a programming course provider)’s “chill lofi beats to code/relax to” and Code Pioneers’ Amazon affiliate promotion of a smart mug:

I should point out that ChilledCow, a long-standing and fan-favourite lofi channel, also began selling its own merchandise in 2018, although this can be perceived as a more organic form of growth compared to the sudden appearance of coding businesses using lofi for marketing purposes in 202031For a more in-depth examination of how artists and uploaders generate income from lofi hip hop radio stations, see Cherie Hu, ‘The Economics of 24/7 Lo-Fi Hip-Hop YouTube Livestreams’, Hot Pod News, 28 January 2020, … Jump to footnote. Moreover, such product advertisements using the aesthetic veneer of lofi sit alongside a variety of political takes on the lofi ‘to [verb] to’ trope.

The Conservative Party (UK) evidently saw the potential for digital communications and youth outreach in their video lo fi boriswave beats to relax/get brexit done to, which mostly features beats by Audio Network’s George Georgia overdubbed with lengthy samples of Boris Johnson speeches32Thanks/complaints to Adam Harper for the link. I assume that the tracks are licensed correctly, though the video uses a Creative Commons Attribution license without any attribution of artist or track names. This subverts a lofi convention to credit … Jump to footnote. Similarly, lo fi merkelwave beats to relax/get nothing done to has racked up 1.7 million views. Warping the format further, the entire speech (not occasional audio snippets) and vdeo recording of an 8½ hour filibuster by Bernie Sanders (and Mary Landrieu) is accompanied by lofi-style beats in Bernie Sanders 8 1/2 hour Filibuster but it’s Lofi. The title here evokes another YouTube trend, such as “The Bee Movie but…”, featuring dramatic edits to humorous effect. Perhaps reductively, lofi is borrowed here as a widely known, stable entity approaching meme status.

Indeed, as lofi has established certain conventions (independent from associations with vaporwave and chillwave, fullwidth text, kind comment sections, cartoon nostalgia, etc.) it has become ripe for appropriation, with a transferable set of aesthetics recognisable in other contexts (e.g., lofi ping pong, advertising, propaganda, comedy). Such appropriations have proliferated as the lofi audience expanded, fuelled by an increase in working and studying from home. Businesses who are aware of this (widely reported) growth and seeking online avenues for promotion have employed lofi mixes and radio stations for commercial benefit. To be fair, the music has always been described as functional music33Amanda Petrusich, ‘Against Chill: Apathetic Music to Make Spreadsheets To’, The New Yorker, 10 April 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/against-chill-apathetic-music-to-make-spreadsheets-to. – to study, or relax, or chill, or code to – but “to be advertised to” represents a clear intrusion of corporate activity into this cultural space.

This has certainly affected the established community and pushed past traditions aside, although it is unclear where such developments will lead. Since the start of the pandemic, lofi’s music and comment sections have evidently been significant for many people as a social space: for expressing concern about COVID-19; for reassuring others about personal safety; for relaxing while studying; for invoking new identities, feeling like a witch or ghost working away late at night; for moving past sentimental recollections of cartoons; and for blowing off steam by jumping on meme trains, true to form for digital-native culture.

References

| ↑1 | Emma Winston and Laurence Saywood, ‘Beats to Relax/Study To: Contradiction and Paradox in Lofi Hip Hop’, IASPM Journal 9, no. 2 (24 December 2019): 40–54, 41. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Adam Krims, Rap Music and the Poetics of Identity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 55. |

| ↑3 | Roy Shuker, Popular Music: The Key Concepts, 4th ed. (London and New York: Routledge, 2017), 148–151 |

| ↑4 | Luke Winkie, ‘How “Lofi Hip Hop Radio to Relax/Study to” Became a YouTube Phenomenon’, VICE, 13 July 2018, https://www.vice.com/en/article/594b3z/how-lofi-hip-hop-radio-to-relaxstudy-to-became-a-youtube-phenomenon. |

| ↑5 | Kemi Alemoru, ‘Inside YouTube’s Calming “Lofi Hip Hop Radio to Relax/Study to” Community’, Dazed, 14 June 2018, https://www.dazeddigital.com/music/article/40366/1/youtube-lo-fi-hip-hop-study-relax-24-7-livestream-scene. |

| ↑6 | Georgina Born and Christopher Haworth, ‘From Microsound to Vaporwave: Internet-Mediated Musics, Online Methods, and Genre’, Music and Letters 98, no. 4 (2017): 601–47, https://doi.org/10.1093/ml/gcx095, 629. |

| ↑7 | Laura Glitsos, ‘Vaporwave, or Music Optimised for Abandoned Malls’, Popular Music 37, no. 1 (January 2018): 100–118, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261143017000599. |

| ↑8 | Adam Harper, ‘Lo-Fi Aesthetics in Popular Music Discourse’ (DPhil Thesis in Musicology, Oxford, University of Oxford, 2014). |

| ↑9 | Adam Harper, ‘What Is Lo-Fi? A Genealogy of a Recurrent Term in the Aesthetics of Popular Music Production’ (Research Seminar, City University London, 9 December 2020). |

| ↑10, ↑19 | Winston and Saywood, ‘Beats to Relax/Study To’, 41. |

| ↑11 | Even though the mix mentioning “ghost” was live for nine months before the cutoff date, the word appears at least twice as often since March. Furthermore, since both videos are on the same channel, the success of “Lo-fi for Witches” may have helped push more traffic towards the “Ghosts” mix. |

| ↑12 | Yuval Palgi et al., ‘The Loneliness Pandemic: Loneliness and Other Concomitants of Depression, Anxiety and Their Comorbidity during the COVID-19 Outbreak’, Journal of Affective Disorders 275 (1 October 2020): 109–11, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.036; Ben J. Smith and Michelle H. Lim, ‘How the COVID-19 Pandemic Is Focusing Attention on Loneliness and Social Isolation’, Public Health Research & Practice 30, no. 2 (30 June 2020), https://doi.org/10.17061/phrp3022008; Tzung-Jeng Hwang et al., ‘Loneliness and Social Isolation during the COVID-19 Pandemic’, International Psychogeriatrics 32, no. 10 (October 2020): 1217–20, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610220000988; Jing Xuan Koh and Tau Ming Liew, ‘How Loneliness Is Talked about in Social Media during COVID-19 Pandemic: Text Mining of 4,492 Twitter Feeds’, Journal of Psychiatric Research, 7 November 2020, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.11.015. |

| ↑13 | This is not lost on Dazed journalist Sophie Atkinson, who describes lofi girl as “the poster girl for responsible coronavirus behaviour for Gen Z and millennials alike”. See Sophie Atkinson, ‘The “24/7 Lo-Fi Hip Hop Beats” Girl Is Our Social Distancing Role Model’, Dazed, 23 March 2020, https://www.dazeddigital.com/music/article/48486/1/the-24-7-lo-fi-hip-hop-beats-girl-is-our-social-distancing-role-model. |

| ↑14 | Lauren McCarthy, ‘Inside #WitchTok, Where Witches of TikTok Go Viral’, Nylon, accessed 11 January 2021, https://www.nylon.com/life/witchtok-witches-of-tiktok. |

| ↑15 | Matteo Cinelli et al., ‘The COVID-19 Social Media Infodemic’, Scientific Reports 10, no. 1 (6 October 2020): 16598, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73510-5. |

| ↑16 | For example, tracks now considered to be vaporwave classics, from albums like フローラルの専門店 (‘Floral Shoppe’) by Macintosh Plus and FINAL TEARS by INTERNET CLUB, are commonly rendered in capitals and include Chinese and Japanese characters. The artist t e l e p a t h テレパシー能力者, first active under that title around 2013, solidifies the trend in vaporwave. These borrowings can be misleading given that ‘lofi’ has different connotations, more akin to ‘DIY’ or ‘non-commercial’, in Tokyo’s contemporary underground jazz and hip hop scenes. |

| ↑17 | Julia Alexander provides various pieces of evidence for an increase in viewership correlated with COVID-19 lockdown measures. See Julia Alexander, ‘Lo-Fi Beats to Quarantine to Are Booming on YouTube’, The Verge, 20 April 2020, https://www.theverge.com/2020/4/20/21222294/lofi-chillhop-youtube-productivity-community-views-subscribers. |

| ↑18 | I write this in reference to the single-word titles of two popular lofi mixes: “NOSTALGIC” (15 million views), uploaded by Neotic, and “Feelings” (11 million views) by Cabvno. Note that both were published in 2017, again implying that the emphasis on this stylised typography is an earlier feature of lofi compared to norms in 2020. |

| ↑20 | BBC News, ‘TV Watching and Online Streaming Surge during Lockdown’, 5 August 2020, sec. Entertainment & Arts, https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-53637305. |

| ↑21 | Prior to this, The Steven Universe character Connie has been depicted emulating the ‘lofi girl’ artwork. See this image hosted on KnowYourMeme. |

| ↑22 | This observation does not mean to downplay the solid ties between other forms of hip-hop and anime. |

| ↑23, ↑25 | Alexander, ‘Lo-Fi Beats to Quarantine to Are Booming on YouTube’. |

| ↑24 | Lynn Jamieson, ‘Personal Relationships, Intimacy and the Self in a Mediated and Global Digital Age’, in Digital Sociology: Critical Perspectives, ed. Kate Orton-Johnson and Nick Prior (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2013), 13–33, https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137297792_2, 15. |

| ↑26 | Winston and Saywood, ‘Beats to Relax/Study To’, 47–48. |

| ↑27 | Note that “safe” frequently appears in the idiom “stay safe”, which may not be as emotionally charged as, say, “depressed”. |

| ↑28 | Abel Brodeur et al., ‘Assessing the Impact of the Coronavirus Lockdown on Unhappiness, Loneliness, and Boredom Using Google Trends’, ArXiv:2004.12129 [Physics], 25 April 2020, http://arxiv.org/abs/2004.12129. |

| ↑29, ↑30 | Alemoru, ‘Inside YouTube’s Calming “Lofi Hip Hop Radio to Relax/Study to” Community’. |

| ↑31 | For a more in-depth examination of how artists and uploaders generate income from lofi hip hop radio stations, see Cherie Hu, ‘The Economics of 24/7 Lo-Fi Hip-Hop YouTube Livestreams’, Hot Pod News, 28 January 2020, https://hotpodnews.com/the-economics-of-24-7-lo-fi-hip-hop-youtube-livestreams/. |

| ↑32 | Thanks/complaints to Adam Harper for the link. I assume that the tracks are licensed correctly, though the video uses a Creative Commons Attribution license without any attribution of artist or track names. This subverts a lofi convention to credit artists and song names appropriately (in the vein of hip-hop’s borrowing culture) even where tracks have been curated without permission. For more on lofi as pirate radio, see Jonah Engel Bromwich, ‘Pirate Radio Stations Explode on YouTube’, The New York Times, 3 May 2018, sec. Arts, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/03/arts/music/youtube-streaming-radio.html. |

| ↑33 | Amanda Petrusich, ‘Against Chill: Apathetic Music to Make Spreadsheets To’, The New Yorker, 10 April 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/against-chill-apathetic-music-to-make-spreadsheets-to. |

2 thoughts on “Beats, Online, and Life: lofi hip hop during COVID-19 (part 2)”