This is the script of a paper I gave at the conference Information Overload? Music Studies in the Age of Abundance, hosted online by the University of Birmingham on 8 September 2021. For more info, see the UKRI AHRC Early Career Leadership Fellowship Music and the Internet: Towards a digital sociology of music.

Introduction

Scholars of music are increasingly turning to the internet as a text-based data source for studying musical experiences, listener values, and virtual communities. A sense of excitement and optimism pervades such work across the humanities, where there has been widespread reference to user comments as indicative of musical reception. Nick Cook writes that analysing the occasional comment posted on video sharing websites is ‘one of the joys of working with Web-based multimedia’,1Nicholas Cook, ‘Beyond Music: Mashup, Multimedia Mentality, and Intellectual Property’, in The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, ed. John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), … Jump to footnote but it is also, to my mind, a burden requiring responsible treatment.

Working with individual comments, there is the risk of answering research questions purely ‘through anecdote’,2Ian Milligan, History in the Age of Abundance?: How the Web Is Transforming Historical Research (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2019), 234. or worse still, cherry-picking to confirm beliefs that are already held. This kind of post hoc justification makes a cunning rhetorical move, presenting a credible argument in the author’s voice then supporting it with a single comment as if proof of a widespread truth. I’ve been guilty of this approach in my past work, so this paper acts as a form of self-critique and a reflection on strengthening methods rather than criticising any particular scholar. It brings into sharp focus the need for careful and considered approaches to using social media data in music studies. In this talk I focus on YouTube comments, but my argument will be applicable to other shortform text data such as Tweets and comments on other platforms.

Improving on the cherry-picking approach I (and others) have used, Áine Mangaoang’s recent monograph applies critical discourse analysis to 2.5% of the total comments on a video. She concludes that it ‘provides a general indication, though limited and limiting as it may be, of the general YouTube reception’.3Áine Mangaoang, Dangerous Mediations: Pop Music in a Philippine Prison Video (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing Inc, 2019), https://doi.org/10.5040/9781501331565, 159. To build upon these understandable limitations, one might turn to tools for collecting larger data sets, like Mike Thelwall’s Mozdeh4Mike Thelwall, Social Web Text Analytics with Mozdeh (Wolverhampton: University of Wolverhampton, 2018). and Bernhard Rieder’s YouTube Data Tools.5Bernhard Rieder, YouTube Data Tools (Version 1.22), 2015, https://tools.digitalmethods.net/netvizz/youtube/.

Big data analysis

Big data analysis and online archival research are proceeding successfully in other fields, where benefits include large bodies of evidence and wide representation of people’s views. Ian Milligan is concerned with training up historians to respond to our digital condition. Web data methods help ‘expand the social history mission of hearing from not only more voices and people, but those who were not traditionally represented in the documentary record’.6Milligan, History in the Age of Abundance?, 233. Noortje Marres identifies that internet data are typically ‘organized or structured in ways that make them highly suitable for controversy analysis’.7Noortje Marres, ‘Why Map Issues? On Controversy Analysis as a Digital Method’, Science, Technology, & Human Values 40, no. 5 (1 September 2015): 655–86, https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243915574602, 658. And the study of affect is flourishing, given that social media has become a place for the expression of emotional – and emotive – language.8Kaarina Nikunen, ‘Media, Emotions and Affect’, in Media and Society, ed. James Curran and David Hesmondhalgh (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019), 323–40. More than simply an opportunity, engaging with online user commentary is urgent, because it’s highly ideological and has far-reaching sociopolitical effects. As David Moats and Nick Seaver put it, ‘despite its many claims to objectivity and legitimacy, data science is politics by other means’.9David Moats and Nick Seaver, ‘“You Social Scientists Love Mind Games”: Experimenting in the “Divide” between Data Science and Critical Algorithm Studies’, Big Data & Society 6, no. 1 (1 January 2019): 2053951719833404, … Jump to footnote As an important example, Mutale Nkonde and colleagues’ study of half a million tweets under the hashtag #ADOS (that is, American Descendants of Slavery) reveals that users deploy the tag with the aims of Black voter suppression (targeted at discouraging votes for the Democratic party).10M. Nkonde et al., ‘Disinformation Creep: ADOS and the Strategic Weaponization of Breaking News’, The Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, 2021, https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-52. They refer to this strategy as disinformation creep.

The benefits of big data analysis are clear, but there are also ethical pitfalls. As scholars of music, we’re trained to think carefully and ethically about how we engage with research participants, but there remains a knowledge gap around responsible engagement with big data. The Association of Internet Researchers guidelines advise consideration of what expectations users have of data shared online, especially the privacy and intended use of their comments.11aline shakti franzke et al., ‘Internet Research: Ethical Guidelines 3.0’, 2020, https://aoir.org/reports/ethics3.pdf. However, few scholars outside of internet studies refer to such guidelines. Moreover, there is often slippage between what is proposed in research grants, ethics statements, and data protection policies and what researchers actually do.12Helen Kennedy, Post, Mine, Repeat: Social Media Data Mining Becomes Ordinary (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 196. Social media research is research with human participants and should meet ethical standards as such.

Essentially, there is a tension at the heart of social media analysis. On the one hand, we want more data to represent a wider range of perspectives and hear more voices. On the other hand, improving access to social media platforms may simply absorb more people into logics of datafication and surveillance. Whether construed as algocracy,13A. Aneesh, Virtual Migration: The Programming of Globalization (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2006). platform capitalism,14Nick Srnicek, Platform Capitalism (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2017). or surveillance capitalism,15Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (London: Profile Books, 2019). it is well accepted in internet studies that the conditions of neoliberalism have left unprecedented power in the hands of Big Tech. When it comes to social media data, the academic ideal of equitable participation could mean subjecting marginalised communities to exploitative and extractive economic processes. Ultimately, if we are in the age of abundance, whose abundance is it? Who is represented in the data, who controls it, who is entitled to use it?

Whose data?

Initiatives for digital inclusion – such as widening social media data sets – are blinkered by optimism for researching positive experiences of the social web. Seeta Peña Gangadharan’s article on digital inclusion stresses the naivety of such approaches (and forgive me for quoting at length): ‘being digitally included means being included in social practices and social activities that harm chronically underserved communities with deep and lasting effects. For the poor, communities of color, indigenous groups, and migrants, being a part of digitally mediated worlds means being made vulnerable in ways that resemble past instances of surveillance and exploitation’.16Seeta Peña Gangadharan, ‘Digital Inclusion and Data Profiling’, First Monday, 13 April 2012, https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v17i5.3821. Gathering data from internet social platforms, even with clear aims of equity and inclusivity, still requires operating within the constraints of ‘cultures of capture’.17Nick Seaver, ‘Captivating Algorithms: Recommender Systems as Traps’, Journal of Material Culture 24, no. 4 (1 December 2019): 421–36, https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183518820366, 7. After all, there could hardly be a more neocolonial term than ‘data mining’.

The term ‘data colonialism’ provides a key reminder that although all people can be harvested for value, it is always the poor – in itself a racialized and gendered categorisation – who are disproportionately affected.18Nick Couldry and Ulises A. Mejias, The Costs of Connection: How Data Is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating It for Capitalism (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2019), 67–8. There is no clearer example of this than the algorithmic oppression detailed by Safiya Umoja Noble, which she defines as ‘algorithmically driven data failures that are specific to people of color and women’19Safiya Umoja Noble, Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism (New York: New York University Press, 2018).. Moreover, her framing highlights a particularly ugly racial dynamic: how internet pseudonymity in some cases may mean the white surveillance of web activities exclusive to people of colour. At scale, consent to observation becomes unattainable, with the assumed public sphere of the social web giving the impression that data are ethically neutral, ‘out there’, free to use. But this strikes at the core of danah boyd’s observation about the difference between ‘being in public and being public’.20danah boyd, It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2014), 57.

The data are already out there

The same criticism of ostensibly ‘public’ data raises issues for open access practices. Implemented well, the open science movement holds promise for breaking down typical boundaries to academic knowledge. All research funded by the Horizon 2020 programme, for example, is required to produce openly accessible publications and strongly encouraged to provide open access to research datasets (with only limited ability to opt-out).21European Commission, ‘Open Access & Data Management’, Horizon 2020 Online Manual, accessed 7 August 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/docs/h2020-funding-guide/cross-cutting-issues/open-access-dissemination_en.htm. Research on social media data essentially operates in a legal grey area, however, because there is still no major consensus on whether written language posted on publicly accessible yet privately owned websites are subject to copyright, intellectual property, and/or data protection laws. The GDPR prohibits data processing of political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, and data concerning sexual orientation,22European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, ‘REGULATION (EU) 2016/679 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free … Jump to footnote but cultural research is likely to include these kinds of information.

It is worth asking whether the use of social media data for research – despite the issues I have discussed – is excusable simply because datafication and surveillance are social norms, ‘nestled into the comfort zone of most people’.23Jose Van Dijck, ‘Datafication, Dataism and Dataveillance: Big Data between Scientific Paradigm and Ideology’, Surveillance & Society 12, no. 2 (9 May 2014): 197–208, https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v12i2.4776, 198. But I do think this is a slightly dangerous line of reasoning. Although the Big Tech oligopoly has already datafied everyday cultural communication through technological mediation, our collection of such data is not a neutral act.24Alison Powell, ‘The Mediations of Data’, in Media and Society, ed. James Curran and David Hesmondhalgh (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019), 121–38. It bears repeating that social media data are subject to the controls of corporate platforms with commercial incentives. However, academic researchers rarely collect with intent to profile or advertise, and it may be that there are two arguments here at risk of conflation: (1) surveillance capitalism requires critical attention, and (2) data analysis methods have certain weaknesses that invite critique. On the latter, there remains a real risk of the skewed datafication of our research towards numbers – falsely implying objectivity25Lisa Gitelman, ed., ‘Raw Data’ Is an Oxymoron (Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: The MIT Press, 2013), https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9302.001.0001. – and interpretations of people’s values by mere traces of online communication. What possibilities remain for ‘doing better with data’ that can be drawn from the web?26Kennedy, Post, Mine, Repeat: Social Media Data Mining Becomes Ordinary, 234.

Paths forward for social media research

There needs to be a balance between open accessibility and user privacy struck by each project. One guiding principle is to collect only the data that you require and share only the data that puts users at no risk. In most cases this means divorcing comments from usernames, although you may want to retain identifying links in a closed dataset. On some topics, it may be wise to prevent reidentification altogether, in which case one might only share individual words and values (such as frequency of word use) rather than text comments in full. The FAIR guidelines of data management suggest the best practice principle of making data ‘as open as possible, as closed as necessary’.27Mark D. Wilkinson et al., ‘The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship’, Scientific Data 3, no. 1 (15 March 2016): 160018, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18. Next, it is important that we publish all research outputs in open access formats, thus making research publicly available online for free. Paywalls only uphold the privatisation and commercialisation of knowledge gleaned from user web data.

Though conventional in digital ethnography, it is wise to avoid quoting particular online commenters complete with usernames. This was a vestige of academic citation norms while the jury was still out, but public opinion here is clear: a two-thirds majority of surveyed participants see even the collection practice as unfair,28Helen Kennedy, Dag Elgesem, and Cristina Miguel, ‘On Fairness: User Perspectives on Social Media Data Mining’, Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 23, no. 3 (June 2017): 270–88, … Jump to footnote let alone reference without consent. Besides, online comments are not qualitatively or epistemologically interchangeable with interview statements or published works. I will suggest an alternative close to the end of this talk for studying semantic data, but this issue is sidestepped by other forms of evidence such as data visualisation.

This may seem like another symptom of the problem of datafication, but there is obvious public gain from available and easily digestible research visualisations. In academic literature, one promising example is the visualisation of online social networks and genre maps that represent the discursive and social mediation of music, as produced by Georgina Born and Christopher Haworth.29Georgina Born and Christopher Haworth, ‘From Microsound to Vaporwave: Internet-Mediated Musics, Online Methods, and Genre’, Music and Letters 98, no. 4 (2017): 601–47, https://doi.org/10.1093/ml/gcx095. Comparably, in public activism, the bottom-up collection and visualisation of civic data – about urban noise or pollution, for example – have been used to apply political pressure to local legislators. This still follows the logic of datafication – the apparent objectivity of diagrams and statistics that politicians find so appealing – yet it ‘opens up the potential for a form of voice through data’.30Powell, ‘The Mediations of Data’, 133.

Critics may still resist the drive towards quantification, and this is key to ensuring our use of data remains resistant to the assemblages of data colonialism. What is necessary, I argue, is a well-considered hybrid model of data analysis and conventional humanities approaches. It is all too tempting to view digital methods as an appealing alternative to musicological or sociological readings, but they are best applied in combination. This heeds Nancy Baym’s call to retain ‘qualitative sensibilities and methods to help us see what numbers cannot’.31Nancy K. Baym, ‘Data Not Seen: The Uses and Shortcomings of Social Media Metrics’, First Monday, 29 September 2013, https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v18i10.4873.

A case study to study/relax to

I’ll now turn to a case study demonstrating a step towards a more rounded methodology. There are still certainly kinks to iron out, and inclusive forms of collaboration will be key to strengthening the approach here. When I think of online music community, to me there is no more wholesome example than the forms of participation observed in the comment sections of lofi hip hop on YouTube. You know the one: lofi hip hop anime chill beats to study and relax to. Kemi Alemoru has characterised lofi on YouTube as ‘one of the kindest communities on the internet’.32Kemi Alemoru, ‘Inside YouTube’s Calming “Lofi Hip Hop Radio to Relax/Study to” Community’, Dazed, 14 June 2018, https://www.dazeddigital.com/music/article/40366/1/youtube-lo-fi-hip-hop-study-relax-24-7-livestream-scene. But I was particularly interested in how the norms of commentary may have changed after a reported influx of new listeners during COVID-19 lockdowns.33Julia Alexander, ‘Lo-Fi Beats to Quarantine to Are Booming on YouTube’, The Verge, 20 April 2020, https://www.theverge.com/2020/4/20/21222294/lofi-chillhop-youtube-productivity-community-views-subscribers. Using Mozdeh, I collected 375 thousand comments on 31 of the most popular mix videos like these. The first step of my analysis was a method of subset word association detection. I used 1st March 2020 as a cutoff point for pre- and during-pandemic samples and analysed them for statistically significant changes in the frequency with which terms were used. That’s purely quantitative. The qualitative aspect is my own interpretation of the terms, which I defined and ordered into specific themes after reading dozens of comments for each term. I compared these to close readings of especially popular comments and the general media commentary on lofi, as in typical sociological research. The combination of these approaches help me to identify cultural values and modes of social connection that characterise lofi hip hop as an online music community.

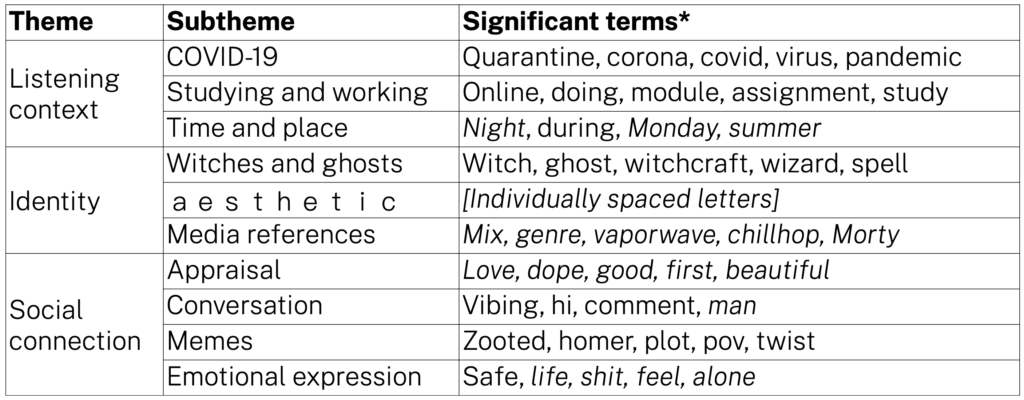

Here is a summary of my findings. Note that the terms in italics are more frequent in the before-pandemic sample.

The main difference in discussion topic is, predictably, COVID-19. Terms like ‘quarantine’ and ‘pandemic’ barely appear before March 2020 and are highlighted by this method as a new and frequent subject of discussion. There has also been an increase in listeners describing their use of the music according to the advertised function: beats to study to. The emphasis on distance learning, as educational institutions the world over transitioned to online teaching, is evident from comments describing novel working practices. With quarantine and studying largely occupying the minds of commenters during the pandemic, it follows that there are fewer references to other times and places compared to the pre-pandemic sample. People describing their current listening contexts in the comments used to be more common.

I’ll give some examples now which either abbreviate comments or rearrange particular terms to obscure the original post. This preserves poster anonymity, protecting the privacy of individual users, while still communicating a ‘general feeling’.34Kennedy, Post, Mine, Repeat: Social Media Data Mining Becomes Ordinary, 118. I avoid introducing new words to maintain an accurate portrait of the sentiments expressed. So, on the theme of time and place, we see reflections like: ‘it’s 1am here, a perfect night to forget about everything’ and ‘this takes me back to the summer of 2015’. The term ‘during’ appeared much more frequently during the pandemic to describe time-bound contexts and functions, as in ‘here during quarantine’ or ‘this kept me going during hours of homework’.

Some other themes are briefly worth discussing. A new mix called ‘lo-fi for witches’ became very popular and prompted a lot of discussion of contemporary witchcraft, comparable to what we might see on WitchTok.35Homework Radio, ‘Lo-Fi for Witches (Only) [Lofi / Calm / Chill Beats]’, YouTube, 27 March 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Hg1Kudd_x4; Lauren McCarthy, ‘Inside #WitchTok, Where Witches of TikTok Go Viral’, Nylon, 6 July 2020, … Jump to footnote There was another ‘for ghosts’. It is tempting to disregard these videos as skewing the sample – no-one really posted about witches or ghosts before – but they are worth some consideration. Witches and ghosts are portrayed in popular media as invisible or outcast loners removed from social connections, committed to domestic hobbies. Lofi listeners experiencing social isolation during the pandemic positively identify with such characters.

My analysis also shows a general reduction in common sentence words, which is surprising given the personal reflections and microfiction that formerly characterised lofi comments.36Emma Winston and Laurence Saywood, ‘Beats to Relax/Study To: Contradiction and Paradox in Lofi Hip Hop’, IASPM Journal 9, no. 2 (24 December 2019): 40–54, 47–8. This trend appears to have been superseded by general introductions, presumably from newcomers to the videos, hence a surge in the use of ‘hi’ and references to other ‘comments’. However – to give a sense of close readings we might use as a point of comparison – two thousand users ‘liked’ a post detailing an apparently relatable scenario: ‘anyone else vibing to this in bed waiting for the coast to be clear at 2am to go grab some cereal?’. This is a vivid image, revealing much about lofi listeners’ domestic life and listening habits. So let’s compare to the journalism profiling lofi, which characterises the audience as ‘traumatized university students’37Luke Winkie, ‘How “Lofi Hip Hop Radio to Relax/Study to” Became a YouTube Phenomenon’, VICE, 13 July 2018, https://www.vice.com/en/article/594b3z/how-lofi-hip-hop-radio-to-relaxstudy-to-became-a-youtube-phenomenon. and the music as something designed to ‘get [them] through the night’.38Michael Wu, ‘What Are Lofi Hip Hop Streams, and Why Are They So Popular?’, Study Breaks, 2 December 2018, https://studybreaks.com/culture/music/lofi-hip-hop-streams-popular/. The popularity of the early-hours cereal comment serves to indicate that there remains a number of identity characteristics and shared practices among the lofi community despite the arrival of new listeners during COVID-19.

There is much more to say on this topic, and I can unpack more of the findings in the questions if there’s interest. Closing with this example of social web data aims to demonstrate the strengths of data analytics in combination with, and not simply instead of, conventional methods of studying music cultures. Minor ethical issues remain, but attempts to make sense of the information overload endemic to the web for the good of the communities in question seem worth the try. Raquel Campos Valverde’s study of online music sharing concludes that users’ social practices rely on ‘internalising musical citizenship duties’.39Raquel Campos Valverde, ‘Musicking on Social Media: Imagined Audiences, Momentary Fans and Civic Agency in the Sharing Utopia’, IASPM Andrew Goodwin Memorial Essay, 12. Given how much musical activity now takes place online, as researchers we must act with a similar responsibility: treat data analysis not as a novelty, but as a form of academic and civic duty for social good. As Couldry and Mejias suggest, we should not underestimate the ‘value of [such] experiments in resistance to data colonialism’.40Couldry and Mejias, The Costs of Connection, 196.

References

| ↑1 | Nicholas Cook, ‘Beyond Music: Mashup, Multimedia Mentality, and Intellectual Property’, in The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, ed. John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 53–76, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199733866.013.0005, 61. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ian Milligan, History in the Age of Abundance?: How the Web Is Transforming Historical Research (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2019), 234. |

| ↑3 | Áine Mangaoang, Dangerous Mediations: Pop Music in a Philippine Prison Video (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing Inc, 2019), https://doi.org/10.5040/9781501331565, 159. |

| ↑4 | Mike Thelwall, Social Web Text Analytics with Mozdeh (Wolverhampton: University of Wolverhampton, 2018). |

| ↑5 | Bernhard Rieder, YouTube Data Tools (Version 1.22), 2015, https://tools.digitalmethods.net/netvizz/youtube/. |

| ↑6 | Milligan, History in the Age of Abundance?, 233. |

| ↑7 | Noortje Marres, ‘Why Map Issues? On Controversy Analysis as a Digital Method’, Science, Technology, & Human Values 40, no. 5 (1 September 2015): 655–86, https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243915574602, 658. |

| ↑8 | Kaarina Nikunen, ‘Media, Emotions and Affect’, in Media and Society, ed. James Curran and David Hesmondhalgh (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019), 323–40. |

| ↑9 | David Moats and Nick Seaver, ‘“You Social Scientists Love Mind Games”: Experimenting in the “Divide” between Data Science and Critical Algorithm Studies’, Big Data & Society 6, no. 1 (1 January 2019): 2053951719833404, https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951719833404, 2. |

| ↑10 | M. Nkonde et al., ‘Disinformation Creep: ADOS and the Strategic Weaponization of Breaking News’, The Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, 2021, https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-52. |

| ↑11 | aline shakti franzke et al., ‘Internet Research: Ethical Guidelines 3.0’, 2020, https://aoir.org/reports/ethics3.pdf. |

| ↑12 | Helen Kennedy, Post, Mine, Repeat: Social Media Data Mining Becomes Ordinary (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 196. |

| ↑13 | A. Aneesh, Virtual Migration: The Programming of Globalization (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2006). |

| ↑14 | Nick Srnicek, Platform Capitalism (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2017). |

| ↑15 | Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (London: Profile Books, 2019). |

| ↑16 | Seeta Peña Gangadharan, ‘Digital Inclusion and Data Profiling’, First Monday, 13 April 2012, https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v17i5.3821. |

| ↑17 | Nick Seaver, ‘Captivating Algorithms: Recommender Systems as Traps’, Journal of Material Culture 24, no. 4 (1 December 2019): 421–36, https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183518820366, 7. |

| ↑18 | Nick Couldry and Ulises A. Mejias, The Costs of Connection: How Data Is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating It for Capitalism (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2019), 67–8. |

| ↑19 | Safiya Umoja Noble, Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism (New York: New York University Press, 2018). |

| ↑20 | danah boyd, It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2014), 57. |

| ↑21 | European Commission, ‘Open Access & Data Management’, Horizon 2020 Online Manual, accessed 7 August 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/docs/h2020-funding-guide/cross-cutting-issues/open-access-dissemination_en.htm. |

| ↑22 | European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, ‘REGULATION (EU) 2016/679 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation)’, 2016/679 § (2016), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016R0679. |

| ↑23 | Jose Van Dijck, ‘Datafication, Dataism and Dataveillance: Big Data between Scientific Paradigm and Ideology’, Surveillance & Society 12, no. 2 (9 May 2014): 197–208, https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v12i2.4776, 198. |

| ↑24 | Alison Powell, ‘The Mediations of Data’, in Media and Society, ed. James Curran and David Hesmondhalgh (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019), 121–38. |

| ↑25 | Lisa Gitelman, ed., ‘Raw Data’ Is an Oxymoron (Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: The MIT Press, 2013), https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9302.001.0001. |

| ↑26 | Kennedy, Post, Mine, Repeat: Social Media Data Mining Becomes Ordinary, 234. |

| ↑27 | Mark D. Wilkinson et al., ‘The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship’, Scientific Data 3, no. 1 (15 March 2016): 160018, https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18. |

| ↑28 | Helen Kennedy, Dag Elgesem, and Cristina Miguel, ‘On Fairness: User Perspectives on Social Media Data Mining’, Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 23, no. 3 (June 2017): 270–88, https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856515592507. |

| ↑29 | Georgina Born and Christopher Haworth, ‘From Microsound to Vaporwave: Internet-Mediated Musics, Online Methods, and Genre’, Music and Letters 98, no. 4 (2017): 601–47, https://doi.org/10.1093/ml/gcx095. |

| ↑30 | Powell, ‘The Mediations of Data’, 133. |

| ↑31 | Nancy K. Baym, ‘Data Not Seen: The Uses and Shortcomings of Social Media Metrics’, First Monday, 29 September 2013, https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v18i10.4873. |

| ↑32 | Kemi Alemoru, ‘Inside YouTube’s Calming “Lofi Hip Hop Radio to Relax/Study to” Community’, Dazed, 14 June 2018, https://www.dazeddigital.com/music/article/40366/1/youtube-lo-fi-hip-hop-study-relax-24-7-livestream-scene. |

| ↑33 | Julia Alexander, ‘Lo-Fi Beats to Quarantine to Are Booming on YouTube’, The Verge, 20 April 2020, https://www.theverge.com/2020/4/20/21222294/lofi-chillhop-youtube-productivity-community-views-subscribers. |

| ↑34 | Kennedy, Post, Mine, Repeat: Social Media Data Mining Becomes Ordinary, 118. |

| ↑35 | Homework Radio, ‘Lo-Fi for Witches (Only) [Lofi / Calm / Chill Beats]’, YouTube, 27 March 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Hg1Kudd_x4; Lauren McCarthy, ‘Inside #WitchTok, Where Witches of TikTok Go Viral’, Nylon, 6 July 2020, https://www.nylon.com/life/witchtok-witches-of-tiktok. |

| ↑36 | Emma Winston and Laurence Saywood, ‘Beats to Relax/Study To: Contradiction and Paradox in Lofi Hip Hop’, IASPM Journal 9, no. 2 (24 December 2019): 40–54, 47–8. |

| ↑37 | Luke Winkie, ‘How “Lofi Hip Hop Radio to Relax/Study to” Became a YouTube Phenomenon’, VICE, 13 July 2018, https://www.vice.com/en/article/594b3z/how-lofi-hip-hop-radio-to-relaxstudy-to-became-a-youtube-phenomenon. |

| ↑38 | Michael Wu, ‘What Are Lofi Hip Hop Streams, and Why Are They So Popular?’, Study Breaks, 2 December 2018, https://studybreaks.com/culture/music/lofi-hip-hop-streams-popular/. |

| ↑39 | Raquel Campos Valverde, ‘Musicking on Social Media: Imagined Audiences, Momentary Fans and Civic Agency in the Sharing Utopia’, IASPM Andrew Goodwin Memorial Essay, 12. |

| ↑40 | Couldry and Mejias, The Costs of Connection, 196. |