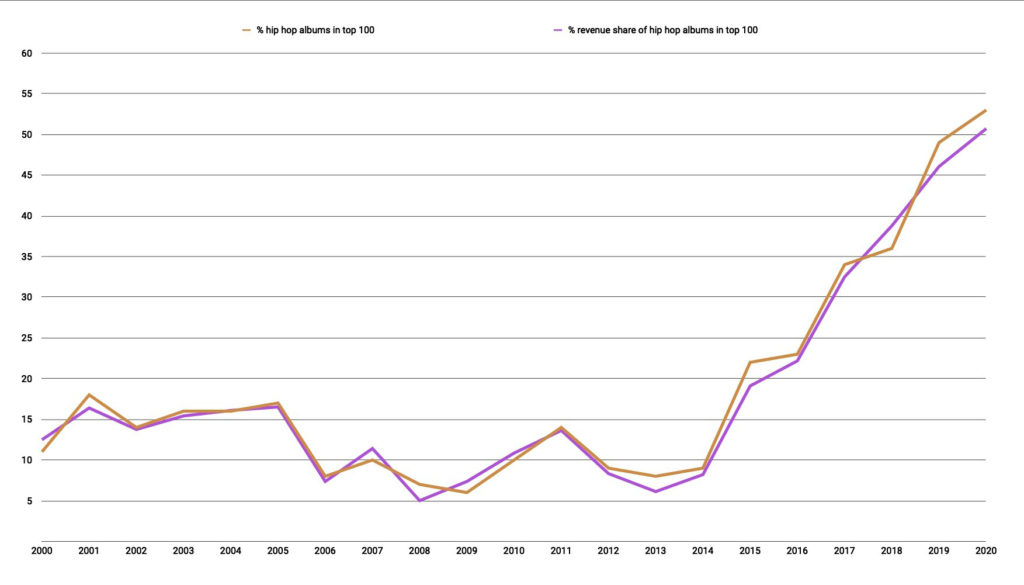

The story of hip hop’s commercial success in the 21st century is one of a steady decline followed by a striking ascent. At the turn of the millennium, hip hop held a major presence on the charts, but never accounted for more than a sixth of the best-selling albums. By the end of 2020, hip hop makes up more than half of the Top 100, an order of magnitude greater than its modest 5% share in 2008. The turning point appears around 2014–2015, where artists charting for the first time include Rae Sremmurd, Iggy Azalea, Future, Macklemore, and Big Sean. Hip hop’s rise to the forefront of mainstream popular music can be attributed to a range of factors, including developments in listening technologies, changes to the ways charts aggregate streaming data, the emergence of a new generation of commercially viable hip hop artists, and a resurgence of popular interest in hip hop music and culture online.

Commercial hip hop was in a sorry state in the late ’00s. Few artists were making best-selling records. They were pushed to the sidelines by pop powerhouses like Lady Gaga, Beyoncé, and Taylor Swift as well as nostalgia sensations such as Amy Winehouse and Michael Bublé. Well-respected hip hop stars like Eminem, Lil Wayne, and Kanye West often placed on the lower end of the bestselling album lists, but could hardly carry the genre alone. The popular appeal and commercial power of The Black Eyed Peas landed them among the highest earners of this period, though their pop-oriented music might be excluded by some as ‘not real hip hop’.1Devitt, Rachel. ‘Lost in Translation: Filipino Diaspora(s), Postcolonial Hip Hop, and the Problems of Keeping It Real for the “Contentless” Black Eyed Peas’. Asian Music 39, no. 1 (2008): 108–34; Lipsitz, George. ‘Reveling in the Rubble: … Jump to footnote

The end of the ’10s, by contrast, sees hip hop bursting with life. In 2020, just as many hip hop artists with ‘Lil’ in their name (6) made top 100 records as artists of any name did in 2009. Add to that another 40 or 50: hip hop now accounts for more than half of the best-selling records each year. A mid-year look at 2021 suggests the trend is set to continue. How did hip hop get here?

Methodology

This post uses publicly available revenue data sourced from MusicID, a music industry data aggregation platform which aims to fuel data storytelling. I present very basic statistics that rely upon much more sophisticated statistical analysis developed by Steve Hawtin et al (who have not been consulted on this article).2See Hawtin, Steve, et al. ‘MusicID Revenue: Music Charts 2000 – 2021’. MusicID, 12 July 2021. http://revenue.musicid.academicrightspress.com/about.htm. MusicID provides a list of the top 100 highest earning albums since 2000. Any of the claims I’m making are about the 100 highest-revenue albums by year, so I can’t really argue anything about hip hop’s overall market share.

I applied genre classification to this list, essentially filtering it to hip hop albums. Genre classification is a slippery thing at the best of times. To avoid prioritising either my own subjective view or the marketing terms endorsed by record labels, I opted for intersubjective, crowd-sourced ratings drawn from Rate Your Music. I referenced every album to create a list of hip hop albums, along with their chart placement and total indicative revenue.

Initially, I included any album that included the classification hip hop (or any hip hop derived genre, such as trap and pop rap) in either the album’s ‘primary’ or ‘secondary’ genres on Rate Your Music. Several albums which feature guest rappers on a couple of tracks, for example, might gain the secondary classification ‘pop rap’. However, this included too many albums that I felt did not represent hip hop in general: these were either pop or R&B albums with a little rapping (sometimes only by featured artists), which garnered the secondary hip hop label.

I therefore restricted the sample to albums with a hip hop genre listed only among the primary genres. This excluded artists such as Justin Bieber, Rihanna, Ariana Grande, Taylor Swift, and Mary J Blige. It also meant removing non-hip hop albums by artists whose work typically falls into the category: Kanye West’s 808s and Heartbreak was the most notable omission. All but Ed Sheeran’s most recent album – an explicitly collaborative project with various hip hop artists – were removed.

Hip hop either side of the millennium

It is not as though hip hop appeared from nowhere. Throughout the ’80s and ’90s, hip hop had decent sales figures.3Coddington, Amy. ‘“Check Out the Hook While My DJ Revolves It”: How the Music Industry Made Rap into Pop in the Late 1980s’. In The Oxford Handbook of Hip Hop Music, by Amy Coddington, edited by Justin D. Burton and Jason Lee Oakes. Oxford … Jump to footnote Although MusicID uses a different methodology to calculate the highest charting albums prior to 2000,4Hawtin, Steve, et al. ‘How Is the Site Is Generated?’ MusicID Impact, 6 April 2020. http://impact.musicid.academicrightspress.com/music/faq_site_generation.htm. it is evident that hip hop records placed well before the millennium. Hip hop first appears on yearly top 100 lists in 1984, represented by the Beat Street soundtrack and Run DMC. Thereafter, hip hop averages 8 yearly hit records throughout the period between 1984 and 2014. 1997 marked a particularly strong year – perhaps the end of the much-disputed ‘Golden Age’5Duinker, Ben, and Denis Martin. ‘In Search of the Golden Age Hip-Hop Sound (1986–1996)’. Empirical Musicology Review 12, no. 1–2 (26 September 2017): 80–100. https://doi.org/10.18061/emr.v12i1-2.5410. – with 14 albums making the top 100.

The early ’00s finds hip hop amid a renewed coast competition. Dr. Dre’s unhelpfully titled 2001, released in November 1999, was the best-selling record of 2000. Meanwhile, his protégé Eminem released a pair of shocking and wildly popular albums that were the fourth and third bestselling of 2000 and 2002 respectively. Southern hip hop was booming, mostly thanks to OutKast and other ‘Dirty South’ stars, while Jay Z and Lil’ Kim put on for the East Coast. Nelly found significant mainstream appeal, with a string of three albums that kept his name in the top 100 between 2000 and 2005.

Eminem returned to the top 20 in 2003 with the soundtrack for 8 Mile, which accompanied the critically acclaimed feature film. 50 Cent, The Black Eyed Peas, and Kanye West also charted major hits in the first half of the decade, while mid-career artists like Nas, Snoop Dogg, and Ja Rule continued to sell well. Notably, 2001 through to 2005 were the best-selling years of hip hop (at least for top 100 albums) before a sudden decline in the mid-to-late ’00s and until an eventual climb in the mid-’10s.

The ‘terrible crisis’ of the 2000s6Rose, T. The Hip-Hop Wars: What We Talk about When We Talk about Hip-Hop and Why It Matters. New York: Basic Books, 2008.

The later 2000s comprise a mishmash of hip hop’s elder statesmen, oddities, and a small handful of breakthrough records. The few constants (with continued notability today) include Eminem, Jay Z, and Lil Wayne. 2005, the last year before a 50% dip in top 100 representation, provides a mixed portrait of hip hop struggling to find direction. Rappers in the prime of their career jostle among retiring stars (Will Smith), one-hit wonders (Pretty Ricky), and the unique Jay Z and Linkin Park mash-up Collision Course. Fresh voices of gangsta rap (Young Jeezy) and Southern club-and-car specialists (Lil Jon) broke the top 100 and became wildly influential in the following years, but charted poorly outside the US.

Part of hip hop’s volatile sales throughout the ’00s can be traced to an industry turn to digital downloads.7Wikström, Patrik. The Music Industry: Music in the Cloud. John Wiley & Sons, 2013. The iPod expanded mobile listening possibilities, taking advantage of increasing storage space to offer listeners unprecedentedly large music libraries. File-sharing and other forms of piracy ran rife, though was not quite as economically damaging as the reporting around Napster’s litigation might suggest. It was the iTunes Store that incited a steadier transition to digital downloads as the dominant format of music sales, simplifying the process of purchasing music at affordable rates from a centralised database. Songs with snappy thirty-second previews excelled in this forum, which may not have suited hip hop’s carefully structured narrative verses. ‘Explicit content’ tags and the domestic sharing of personal computers might have prevented younger listeners from purchasing hip hop in its newly digital form despite the genre’s large suburban audience.

Veering into critical territory, some of the albums selling well in hip hop’s weaker commercial years warrant brief discussion. I already mentioned the pop-friendliness of The Black Eyed Peas, but 2007 and 2011 also feature some questionable entries. In the top 20, 2007 boasts Fergie, Akon, Timbaland, and Gwen Stefani’s The Great Escape. While few hip hop heads would take issue with Timbaland’s no. 10 placement with the compilation-cum-collaboration Shock Value, Akon has primarily made his name for sung-through R&B. Gwen Stefani’s Sweet Escape certainly – or should that be undoubtedly – leans into hip hop more than No Doubt, but remains (to my ears at least) a pop oriented album. Similarly, hip hop barely registers on Fergie’s The Dutchess, which sold extremely well off the back of the number-one piano ballad ‘Big Girls Don’t Cry (Personal)’. My issues here may point to problems with Rate Your Music’s genre rating system, but it is hardly up to me to determine what is or isn’t hip hop.

More noteworthy is the compromises made around 2010 to position hip hop within a commercially successful frame. The key, it seems, was stylistic combination with electronic dance music and pop. 2011 perhaps makes this point more clearly, with the rather critically-maligned8Morrice, Amy. ‘Album Review: LMFAO – “Sorry For Party Rocking”’. NME (blog), 19 July 2011. https://www.nme.com/reviews/reviews-lmfao-12216-311057. LMFAO breaking the top 10 in the UK, France, Canada, and Australia. The music is justifiably classified with the ‘pop rap’ tag, though I do wonder how widely this music is heard as a form of hip hop in the pop-friendly direction that LMFAO take it. Nonetheless, it sits alongside other best-selling EDM-pop-plus-rap like Pitbull’s Planet Pit. Entries like this dry up quickly after 2012.

Cloud rap? Hip hop in the streaming era

Following this uncertain period, new artists made headway as popstars with a closer relationship to hip hop. Here we see the likes of Drake, Nicki Minaj, and Tyga chart. Torchbearers for West Coast and East Coast rap like Kendrick Lamar and A$AP Rocky, respectively, appear shortly after. They compete with renewed efforts from Kanye West (Yeezus) and Jay Z (Magna Carta: Holy Grail) in the wake of the influential collaborative album Watch the Throne.9See Rollefson, J. Griffith. Critical Excess: Watch the Throne and the New Gilded Age. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2021.

The early-to-mid ’10s not only sees a new generation of rap artists take centre-stage but coincides with another shift in music consumption, this time from digital downloads to on-demand streaming.10Johansson, Sofia, Ann Werner, Patrik Åker, and Greg Goldenzwaig. Streaming Music: Practices, Media, Cultures. Routledge, 2017. While statistics indicate the hip hop listener base grew during this period, the gradual inclusion of streams in chart placement calculations particularly helped expand hip hop’s commercial horizon. In 2013, Billboard’s Hot 100 rankings blended sales, radio airplay, and streaming, with roughly a quarter of the weighting allocated to the song’s streaming performance. By 2019, streaming carries the heaviest weighting (although some might argue it still underestimates the dominance of streaming, at least in Western music economies).

The increased ease of streaming alongside a general shift away from ownership and towards cloud-based access has helped propel hip hop to a dominant position in the global music economy. Artists taking advantage of this development in music consumption include Rae Sremmurd, G-Eazy, and Fetty Wap, who make pop-friendly hip hop targeted at large mainstream audiences. Each of these artists produced bestselling records for the first time in 2015, which marked a significant upturn in hip hop’s commercial success: this is the first year where over 20 hip hop albums placed, although the majority of them appeared in the lower half of the top 100. 2016 saw just as many albums place (one more, to be precise), though half of them earned a position in the top half of the year-end bestsellers, massively boosting hip hop’s indicative revenue.

Notable among the 2016 bestsellers is Lin-Manuel Miranda’s hip hop musical Hamilton. While it was a widespread cultural phenomenon, commentators have highlighted problems such as the show’s uncritical positioning of slaveowners.11Kajikawa, Loren. ‘“Young, Scrappy, and Hungry”: Hamilton, Hip Hop, and Race’. American Music 36, no. 4 (2018): 467–86. https://doi.org/10.5406/americanmusic.36.4.0467. These critiques have hardly dampened its chart success, with one of the most sustained runs for any album classified as hip hop (#12 in 2016, #15 in 2017, #18 in 2018, #37 in 2019, #26 in 2020). The stage show’s momentum running in theatres across the globe has surely supported both record sales and streams of the live recording. Most of Hamilton’s songs have broken the one-hundred-million stream mark on Spotify.

Hip hop as the top dog of pop

Alongside Hamilton – by far the most popular stage show incorporating hip hop elements – other mainstream appearances of hip hop have helped to establish a larger listener base for the genre. The widespread influence of hip hop on digital culture more generally, from social media dance crazes12Gaunt, Kyra D. ‘Youtube, Twerking, and You: Context Collapse and the Handheld Copresence of Black Girls and Miley Cyrus’. In Voicing Girlhood in Popular Music, edited by Jacqueline Warwick and Allison Adrian, 208–32. New York: Routledge, 2016. … Jump to footnote to video game experiences,13Stuart, Keith. ‘More than 12m Players Watch Travis Scott Concert in Fortnite’. The Guardian, 24 April 2020, sec. Games. https://www.theguardian.com/games/2020/apr/24/travis-scott-concert-fortnite-more-than-12m-players-watch. has cemented hip hop as ‘the world’s dominant youth culture’.14Sanneh, Kelefa. Major Labels: A History of Popular Music in Seven Genres. Canongate Books, 2021. It is therefore unsurprising that the last couple of years have seen a striking increase in the number of hip hop records among the top 100.

The predominance of hip hop has led Kelefa Sanneh to point out that, during the 2010s,

It sometimes seemed as if hip-hop was popular music, with everything else either a subgenre or variant of it, or a quirky alternative to it. On streaming services especially, you might look at the chart and see that just about all the most popular songs in America were hip-hop, or hip-hop-ish.15Sanneh, Kelefa. Major Labels: A History of Popular Music in Seven Genres. Canongate Books, 2021.

This observation maps on neatly to the state of the charts at the very end of the decade, as hip hop occupied more and more of the top 100: 22 spots in 2015, 23 in 2016, 34 in 2017, 36 in 2018, 49 in 2019, and 53 in 2020. 2021 looks set to continue this upward trend.

2020 also marks the first time more than 5 hip hop albums by women made it to the best-sellers list (6, including female performers on Hamilton and Dreamville’s Revenge of the Dreamers III). Though more women are achieving top 100 records than ever before, there is no real progress in terms of gender parity. Despite first-time placements of new solo artists like Doja Cat and Megan Thee Stallion, men dominate hip hop albums placing on the top charts, and women – whether as part of a majority-male group or performing a single song on a compilation album – remain marginal.

Two beliefs about the digitalisation of music sit in tension.16See Hansen, Kai Arne, and Steven Gamble. ‘Saturation Season: Inclusivity, Queerness, and Aesthetics in the New Media Practices of Brockhampton’. Popular Music and Society 44, no. 5 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2021.1984019. One, that internet platforms level the playing field for emerging artists. Two, that top-tier superstars have a stranglehold over the market. Could both be true? Looking at hip hop albums among the yearly bestsellers suggests that opportunities for new artists are broadening just as established artists are retaining oligopolistic control. The list of artists achieving best-selling records in the last few years is diversifying (with dozens of first-time charters) while hip hop heavyweights continue to cement their dominant positions. In 2020, Post Malone holds three spots in the top 40. Drake and Juice WRLD similarly have three of the top 100 spots each, while DaBaby, Eminem, Kendrick Lamar, Lil Uzi Vert, Pop Smoke, and Rod Wave each hold two.

All The Way Up?

Hip hop in the postmillennial era has always been present among the top 100 yearly bestselling albums, though this position has not exactly been stable. Around 2000, the genre starts strong, slowly declines, shows signs of recovery around 2011, dips again, then rises uninterrupted from 2015. From 2000 to 2014 hip hop bestsellers sustained an average market share of around 10% on average, never producing fewer than 6 or more than 18 records among the top 100. Since the mid ’10s, however, hip hop has been on a tear.

The record industries have experienced a tumultuous period for music consumption technologies, with shifts taking place more quickly than throughout the 20th century. Despite popular narratives about a ‘Golden Age’ era during the ’80s to ’90s and a corporate, mainstream ‘sellout’ period around the turn of the millennium, hip hop has never been as commercially viable as right now. This serves to contradict journalistic concerns around the streaming era placing the album format under threat,17Hesmondhalgh, David. ‘Streaming’s Effects on Music Culture: Old Anxieties and New Simplifications’. Cultural Sociology, 16 June 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/17499755211019974. or at least suggests that hip hop is one of the more conservative genres with regard to format (though one would imagine the culture of mixtapes has been de-emphasising the album for decades).

While it is worth celebrating that more female hip hop artists appear among the top 100 than ever before, the genre is still significantly male-dominated at the highest-earning level. Hip hop multimedia continues to achieve commercial success, from Beat Street through Space Jam to Hamilton. If Nas was right to claim, in 2006, that ‘Hip Hop Is Dead’, it is evident that by 2020 it has been resurrected. While the song offered a critique of the genre’s commercialisation, it actually heralded a serious decline in hip hop’s top 100 revenue in the later 2000s. And yet, its producer, will.i.am, was one of the few to provide a lifeline. Hip hop’s ability to absorb elements of pop and electronic dance music have contributed to its contemporary position holding at least half of the yearly bestselling albums. The striking success of the genre since the mid-2010s has seen hip hop move – to borrow another hit title – ‘All The Way Up’.

References

| ↑1 | Devitt, Rachel. ‘Lost in Translation: Filipino Diaspora(s), Postcolonial Hip Hop, and the Problems of Keeping It Real for the “Contentless” Black Eyed Peas’. Asian Music 39, no. 1 (2008): 108–34; Lipsitz, George. ‘Reveling in the Rubble: Where Is the Love?’ In Musicological Identities, edited by Steven Baur, Raymond Knapp, and Jacqueline Warwick. Routledge, 2008. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See Hawtin, Steve, et al. ‘MusicID Revenue: Music Charts 2000 – 2021’. MusicID, 12 July 2021. http://revenue.musicid.academicrightspress.com/about.htm. |

| ↑3 | Coddington, Amy. ‘“Check Out the Hook While My DJ Revolves It”: How the Music Industry Made Rap into Pop in the Late 1980s’. In The Oxford Handbook of Hip Hop Music, by Amy Coddington, edited by Justin D. Burton and Jason Lee Oakes. Oxford University Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190281090.013.35. |

| ↑4 | Hawtin, Steve, et al. ‘How Is the Site Is Generated?’ MusicID Impact, 6 April 2020. http://impact.musicid.academicrightspress.com/music/faq_site_generation.htm. |

| ↑5 | Duinker, Ben, and Denis Martin. ‘In Search of the Golden Age Hip-Hop Sound (1986–1996)’. Empirical Musicology Review 12, no. 1–2 (26 September 2017): 80–100. https://doi.org/10.18061/emr.v12i1-2.5410. |

| ↑6 | Rose, T. The Hip-Hop Wars: What We Talk about When We Talk about Hip-Hop and Why It Matters. New York: Basic Books, 2008. |

| ↑7 | Wikström, Patrik. The Music Industry: Music in the Cloud. John Wiley & Sons, 2013. |

| ↑8 | Morrice, Amy. ‘Album Review: LMFAO – “Sorry For Party Rocking”’. NME (blog), 19 July 2011. https://www.nme.com/reviews/reviews-lmfao-12216-311057. |

| ↑9 | See Rollefson, J. Griffith. Critical Excess: Watch the Throne and the New Gilded Age. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2021. |

| ↑10 | Johansson, Sofia, Ann Werner, Patrik Åker, and Greg Goldenzwaig. Streaming Music: Practices, Media, Cultures. Routledge, 2017. |

| ↑11 | Kajikawa, Loren. ‘“Young, Scrappy, and Hungry”: Hamilton, Hip Hop, and Race’. American Music 36, no. 4 (2018): 467–86. https://doi.org/10.5406/americanmusic.36.4.0467. |

| ↑12 | Gaunt, Kyra D. ‘Youtube, Twerking, and You: Context Collapse and the Handheld Copresence of Black Girls and Miley Cyrus’. In Voicing Girlhood in Popular Music, edited by Jacqueline Warwick and Allison Adrian, 208–32. New York: Routledge, 2016. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315689593. |

| ↑13 | Stuart, Keith. ‘More than 12m Players Watch Travis Scott Concert in Fortnite’. The Guardian, 24 April 2020, sec. Games. https://www.theguardian.com/games/2020/apr/24/travis-scott-concert-fortnite-more-than-12m-players-watch. |

| ↑14, ↑15 | Sanneh, Kelefa. Major Labels: A History of Popular Music in Seven Genres. Canongate Books, 2021. |

| ↑16 | See Hansen, Kai Arne, and Steven Gamble. ‘Saturation Season: Inclusivity, Queerness, and Aesthetics in the New Media Practices of Brockhampton’. Popular Music and Society 44, no. 5 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2021.1984019. |

| ↑17 | Hesmondhalgh, David. ‘Streaming’s Effects on Music Culture: Old Anxieties and New Simplifications’. Cultural Sociology, 16 June 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/17499755211019974. |